First published September 2021 | Words and photos by Vietnam Coracle

This post was last updated 3 years ago. Please check the comments section for possible updates, or read more on my Updates & Accuracy page.

During the latest wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in Vietnam, I formed a new relationship with instant noodles. Vietnam’s fourth wave of Covid-19 infections – by far the worst since the pandemic began – has led to many strict lock-downs across the nation. Sadly, food for millions of people has been desperately scarce; for others, it’s simply been lacking in variety and choice. I am fortunate to be in the latter group: food has been available, but there hasn’t been the usual plethora of delicious and affordable options lining the streets, such as stalls selling hearty broths and noodle soups, or local rice eateries serving dozens of reasonably-priced dishes, or fresh produce markets offering myriad vegetables, fruits, meat and fish for home-cooking. Pot noodles, however, have been been readily available throughout the lock-downs.

*Pandemic Relief: If you’d like to donate to help Vietnam’s pandemic relief effort, please read this

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Pot Noodle

For most of the months since the fourth wave began, I’ve been on the island of Phu Quoc, unable to leave (not that I’d want to, even if I had the choice). For some six weeks, the island was under a relatively strict form of lock-down, called Directive 16. During this time, I had access to one convenience store and a couple of market stalls, but no kitchen. I also had access to a decent – but pricey – restaurant. To save costs, I only ate at the restaurant once a week; the other six days I made do with whatever was available from the convenience store and stalls within my restricted zone. More often than not, this was pot noodles. Reluctant at first, I slowly came to like and look forward to this pandemic staple. And it’s not only me: for millions of people across the nation, instant noodles have been a keystone of their pandemic diet.

Even before the pandemic hit, Vietnamese consumed (and produced) an enormous quantity of instant noodles. But, as the pandemic has worn on, domestic consumption of instant noodles has grown by nearly 30%. Vietnamese now consume over 7 billion servings a year, making them the world’s third largest consumer of instant noodles, behind China and Indonesia (both of whom have much larger populations than Vietnam). There are currently around 50 instant noodle companies on the market in Vietnam, and domestic brands alone export to 40 foreign markets. Indeed, the richest man in Vietnam, Phạm Nhật Vựong – founder and chairman of Vingroup, the largest private conglomerate in the country, and the first ever Vietnamese billionaire – began his road to riches with an instant noodle business in Ukraine.

*Disclaimer: Information and statistics in this article are based only on my limited reading and understanding of various sources and conversations with people: I am not a journalist and I cannot vouch for the accuracy of such details on this page.

As with many countries in East Asia, the Vietnamese connection with instant noodles runs deep. To a certain extent, instant noodles are egalitarian and classless: affordable for anyone, consumed by everyone. Office workers, labourers, teachers, students, young and old – very few Vietnamese people I know would refuse a bowl of instant noodles. Cheap, convenient, hot and filling (if not nourishing), instant noodles can be prepared quickly, consumed on the go and without the need for any cooking utensils, cutlery or crockery. For these reasons, pot noodles are a favourite in any situation where time, money or equipment are in short supply, such as on any form of transportation. Back in pre-Covid times, I’d encounter instant noodles almost daily while doing research for this website: on long-haul buses, sleeper trains, in airports, on hikes, at roadside eateries, and even on the dozens of short ferry hops across the many branches of the Mekong River in the delta region. Prior to the pandemic, however, I only ate instant noodles on camping trips.

Alarmingly cheap, some packets of instant noodles are sold for 6,000-10,000VND ($0.25-$0.50). Bought in bulk, the price per pot is even lower. As a result, instant noodles are often a staple of lower-income families, labourers and students. When I travel around the country, I notice the high consumption rate among the large forces of itinerant construction workers, who travel from site to site across the nation – often with their families (including young children) in tow – building the infrastructure and development projects that have defined the last 20-30 years of industrialization in Vietnam. In many cases – especially among children – instant noodles are eaten ‘raw’, as you might a bag of potato chips. Because of their versatility, durability, convenience and low cost, pot noodles are the first food to be distributed to people in need during emergencies in Vietnam, such as severe flooding in typhoon season or the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, when many millions of people have had to rely on supplies from government aid and private charities.

Before the fourth wave of the pandemic, I didn’t feel as positively about instant noodles as many Vietnamese do. For the most part, I avoided them as much as I could. I detested their chemical aroma, the sachets of dubious crystalized ‘flavour dust’, the high salt and MSG content, and their lack of nutritional value – especially in a nation where hearty, well-balanced, complex, fresh and delicious bowls of real noodles are ubiquitous. How sad, I thought, to see students in the flush of youth sitting under the white, X-ray glare of convenience store fluorescent lights, devouring instant noodles from a plastic bucket full of artificial flavours, when they could be enjoying a nutritious bowl of home-cooked bún bò Huế packed with fresh ingredients from a porcelain bowl next door. I also resented the amount of single-use plastic involved in the consumption of pot noodles: the wrapping, the pots, the sachets, the plastic cutlery. Sadly, much of the trash I see washed up on the nation’s beaches and riverbanks, or strewn over the forest floor is instant noodle-related.

I have always considered instant noodles to be junk food and pretty unhealthy, but I’m not certain what the general attitude in Vietnam is. As I was writing this article, news broke that pesticides had been found in certain batches of Hảo Hảo, a Vietnamese brand of instant noodles sold globally. Packets of Hảo Hảo noodles were quickly taken off the shelves in countries around the world. The story garnered a lot of attention in the domestic press and on social media channels. Suddenly, whenever I told my Vietnamese friends I was eating more pot noodles as a result of the pandemic and that I intended to write about them, the first thing people mentioned was the danger they posed to my health. However, once we’d established Hảo Hảo was not my preferred brand, the panic was over and the assumption was that instant noodles were no threat to my health whatsoever – as long as they weren’t the brand tainted by pesticides.

*Please Support My Site: I never receive payment for anything I write: all my content is free to read and independently financed. There’s no sponsored content whatsoever. If you like this article, please consider making a donation or becoming a patron. Thank you, Tom

For many people in Vietnam, instant noodles are a comfort food: a pleasurable, hot snack; filling, satisfying and often imbued with a certain nostalgia – bringing back memories of childhood and student days, of picnics and journeys, and of simpler times. Like most comfort food, pot noodles are all about pleasure, not health or nutrition. Indeed, comfort food is something that we’ve all needed (and probably overindulged in) during the pandemic.

My new-found appreciation of instant noodles can be traced back to the day I arrived on Phu Quoc Island, marking the beginning of the fourth wave of the pandemic. The ferry crossing from the mainland to the island usually takes a couple of hours. My ferry, however, sputtered to a halt about 30 minutes into the voyage. An hour adrift in the Gulf of Thailand later, we sailed back – very slowly – to the mainland. As we waited on the quay for a replacement ferry, a storm blew in and the rain fell heavily on us. Finally, dusk drew over the ocean, the storm passed, and our ferry left (again) for Phu Quoc Island. Conditions at sea, though, were as rough as I’ve ever known them in 13 years of making the crossing. Tired, wet, mildly seasick and hungry, I capitulated and bought the only food available on the boat: pot noodles. Balanced precariously on the edge of my porthole, I nursed the plastic pot of piping hot noodles while trying to type an email to my parents on my laptop. Soothing my hunger, picking up my mood, and rejuvenating my spirit as the ship rolled on the heavy seas and the last orange glimmer of daylight disappeared over the horizon, I finally found comfort in instant noodles.

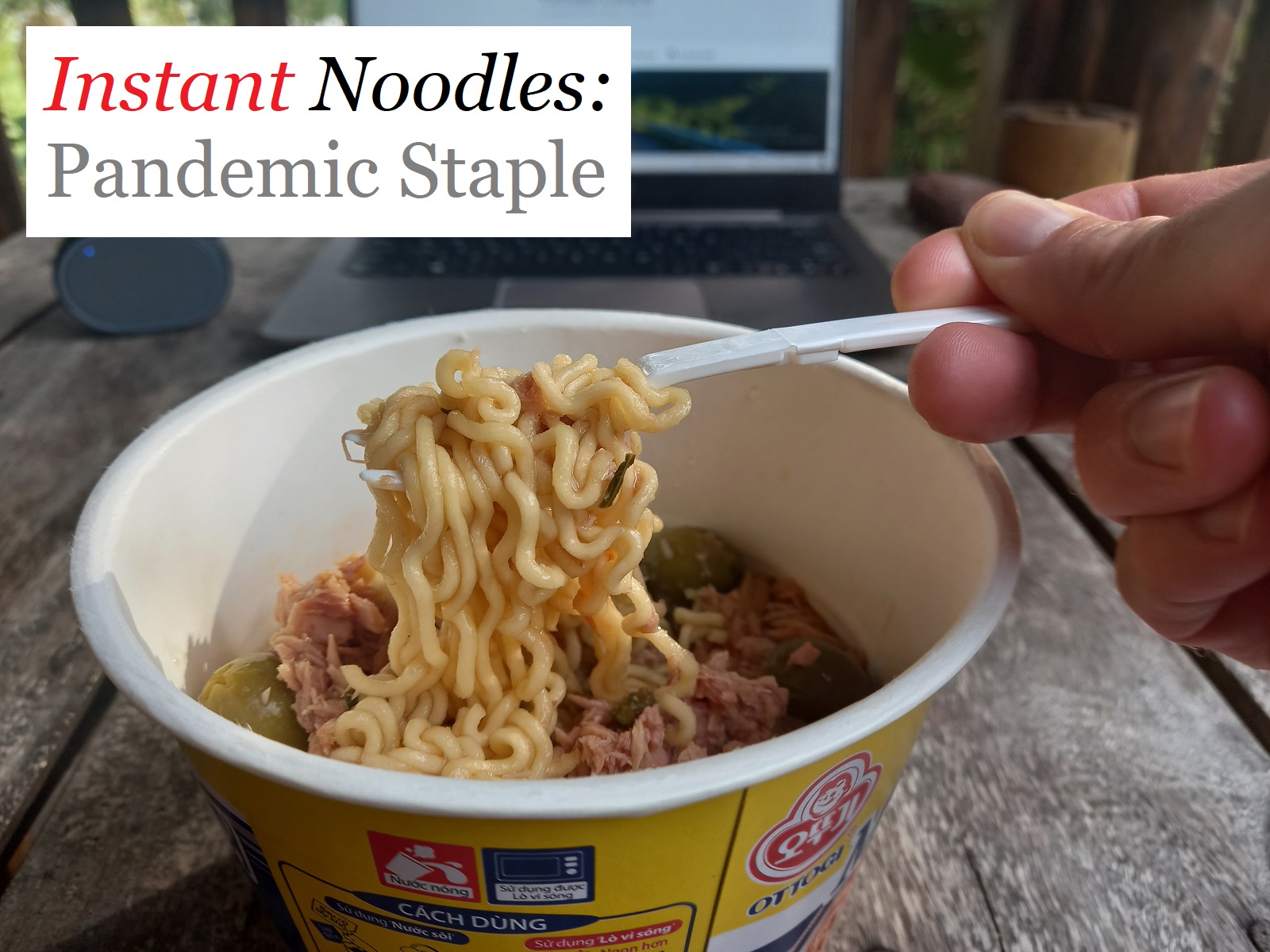

The ferry eventually got me to Phu Quoc Island, where I’ve been ever since. Over the course of that time, instant noodles have become a regular part of my diet. However, I always enhance my pot noodles by adding extras from whatever else is available in the convenience store. Generally, this includes canned tuna, Spam, cheese and canned olives. Adding these extras makes the noodles go a bit further and gives them slightly more nutritional value. It’s a hot, filling, satisfying, flavourful and cheap meal. I don’t need a kitchen, or a cooker, or any utensils at all: I only need a kettle.

Vietnamese call instant noodles by several names: mì gói (‘packet noodles’), mì ăn liền (literally ‘eat immediately noodles’), or mì tôm (‘shrimp noodles’), so called because the design on the packet of one of the first and most popular brands of instant noodles featured a large shrimp. When no other ingredients are available – such as on a ferry – Vietnamese will eat pot noodles as is. But, oftentimes, instant noodles are used in home-cooking as a base to which to add beef or pork, fresh herbs or vegetables and much more. There are even some famous and delicious Vietnamese broths that are commonly poured over instant noodles. One such example is bò kho – an aromatic, mildly spiced beef stew – which, for me, is best served with mì gói.

Despite my new-found, pandemic-inspired relationship with pot noodles, I don’t love them and I don’t intend to continue my current consumption rate post-pandemic. I do, however, understand the appeal, convenience, comfort and, in some cases, necessity of instant noodles. But, as far as I’m concerned, my tastes are better satisfied, my money better spent, and my body and soul better nourished by any number of the extraordinary, magical, mystical bowls of real noodle soups sold on the sidewalks of every village, town and city in Vietnam. It’s important to note, too, that many of these real noodle soups are just as affordable as the instant variety. As long as real noodle soups are sold on the nation’s streets, instant noodles will be a distant second choice for me.

*Disclosure: I never receive payment for anything I write: my content is always free and independent. I’ve written this article because I want to: I find the subject interesting and I want my readers to know about it. For more details, see my Disclosure & Disclaimer statements and my About Page

Thank you Tom, very interesting note about instant noodles. Could agree with most of presented info and opinions about subject but it’s not cheap in all. Yes it cheap if you buy 1-2 packs in week but for every day consume is not. Just calculate the price for 1kg 🙂 Also hava a question about main component of noodles that occurs more often. Is it rice flour or wheat? What type do you preffer and is any price defference between?

Hi Alexander,

In general I think instant noodles are usually wheat flour in Vietnam – but there are many different types available here. Actually, a couple of the most famous and popular brands are potato starch as far as I know.

In terms of price, when you consider a pot of instant noodles as one meal, it is about as cheap as you can get in Vietnam: even a rice lunch at a workers’ canteen would be twice the price as a pot of instant noodles. But, yes, buying in bulk, raw rice would be cheaper.

Best,

Tom

Another well inspired article, thanks Tom.

I’ve never eaten instant noodles when I was traveling in Vietnam, for the exact same reasons you mention here. Vietnamese street food is so much more delicious and inspiring than industrial food: luckily, I’ve never been in a situation where I had to opt for it. That being said, in the context of the pandemic it makes a lot of sense.

I hope Vietnam will soon come back to a normal way of life so that you can enjoy all the treasures of street food again.

Keep well,

Tom

Thanks, Tom.

Luckily, where I am now on Phu Quoc Island, restrictions have been lifted and I can now go out and eat REAL noodles on the street again 🙂

However, much of the rest of the country is still under lock-down.

Best,

Tom