Last updated August 2021 | Written by Vietnam Coracle

This post was last updated 3 years ago. Please check the comments section for possible updates, or read more on my Updates & Accuracy page.

INTRODUCTION | ARTICLE | MAP | RELATED POSTS

In Vietnam, the period of time we’re currently living through, during which the world struggles to contain Covid-19, is known as mùa dịch: ‘pandemic season’. Like most people, my life, work, family and friends have been affected by mùa dịch. And, like most people, the ‘pandemic season’ has caused me to reflect on many different things. This page is an attempt to organize my thoughts, experiences and emotions during mùa dịch into a personal narrative covering much of the last 18 months. I’ve divided ‘pandemic season’ in Vietnam into three phases: ‘Pre-Covid’, ‘Lock-Down’, and ‘Post-Virus’. A country of nearly 100 million people which shares a border with China (where the outbreak first occurred), Vietnam is currently struggling to contain a fourth (and by far the worst) wave of the pandemic. At the time of latest update (August 21, 2021), there were more than 323,000 reported cases and over 7,500 deaths nationwide. Despite the resurgence of the virus since May 2021, Vietnam has still been highly successful in its pandemic response and I feel very fortunate to have spent ‘pandemic season’ here.

[Back Top]

PANDEMIC SEASON IN VIETNAM

Preface: This page is my account of what it’s been like to live through mùa dịch (‘pandemic season’) in Vietnam: part travelogue, part personal narrative, and part analysis of Vietnam’s strategy to contain Covid-19. I don’t claim to have any expert knowledge on the subject of coronavirus, nor am I suggesting that my ‘pandemic season’ experience has been especially unique. Indeed, there’s no doubting my comparatively fortunate and secure circumstances during this unstable period. But I hope that, for readers outside Vietnam, this account may shed some light on how the country has been dealing with the virus; and, for readers inside Vietnam, it may be interesting to hear someone else’s experience and interpretation of events that are already familiar to you. This is a long-form piece of writing, including illustrations and maps. (Please also read my Disclaimer & Disclosure.)

Structure: This is a three-part narrative: a ‘Covid trilogy’. Part 1: Pre-Covid focuses on the lead-up to the virus, the initial phase of the Covid outbreak in Vietnam, and the weeks preceding nationwide lock-down. Part 2: Lock-Down details my experiences during the first national lock-down in April, 2020. Part 3: Post-Virus will be published whenever the time comes.

It’s Not Over: Mùa dịch (‘pandemic season’) seems particularly apt, as it suggests recurrence and the possibility that this virus may return, or even become part of an annual cycle. Conversely, by using the definite article – ‘the pandemic’ – the implication is of a finite period with a defined beginning and end: a one-off event, after which it will all be over and everything will go back to normal. By writing this ‘Covid trilogy’, I’m not suggesting the pandemic is over in Vietnam: mùa dịch may return, as is the nature of ‘seasons’. I’m not complacent and neither, I hope, is anyone else.

- PART 1: Pre-Covid

- PART 2: Lock-Down

- PART 3: Post-Virus

MAP:

Part 1: Pre-Covid

*Disclaimer & Disclosure: This is not a piece of journalism. Rather, it’s a personal recollection & an attempt to tell a story based on my experience over the past few months. In this account, I am most concerned with the narrative & my own emotional & intellectual response to, opinions of, and reflections on, the events in Vietnam since January 2020. I am less concerned with exact figures & dates. If you wish to fact-check anything in this piece, it’s easily done with a simple Google search, such as, ‘When was Vietnam’s first confirmed Covid-19 case?’ or ‘On which date did mandatory quarantine for all international arrivals commence?’ etc. I have no affiliation with the Vietnamese government nor do I belong to any other political group in Vietnam or abroad. The opinions & ideas expressed in this article are my own & I have not received payment of any kind. Much has now been written about Vietnam’s response to the virus (both positive & negative) in the domestic & international press, most of which is available online for free. I’d encourage anyone who’s interest is sparked by anything written on this page, to read more on the subject. My account is only one perspective.

PART 1: Pre-Covid

Waiting to greet my parents outside the arrivals hall at Tan Son Nhat Airport, I felt anxious. It was a sun-filled morning in mid-February and my parents were due to arrive in Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) to visit me. We only see each other once or twice a year, so there’s a certain amount of emotional apprehension whenever I meet my parents off the plane. But this was different: this was a collective nervousness and uncertainty, shared by everyone else on that bare, modern, bright and hushed arrivals concourse. At that time, no one in the arrivals hall knew if they had just flown into a dangerous situation, any more than the people directly above, in the departures hall, knew if they were flying away from one. But popular opinion at that time would have concluded that those in the departure hall heading west would likely be safest. The virus had yet to take hold in Europe and America, and, even though Vietnam appeared to have it under control, the coronavirus was still broadly viewed as an Asian epidemic.

At the airport, my parents and I climbed into a taxi, then drove through the early morning traffic and exhaust-haze toward the high-rises of downtown District 1. In the decade since I’ve been living in Vietnam, my parents make the journey from the U.K at least once a year, usually around December-March, when the weather back home is cold, damp and dark, but in southern Vietnam it’s warm, dry and sunny. My parents had come prepared: bringing with them a supply of masks and handwash. Back then, the U.K was starting to panic-buy products such as these. Vietnam, on the other hand, had already gone through the panic-buying stage. After a brief period of scarcity, the government – quickly realizing the need for more masks and handwash – increased supplies, and both were now readily available in most pharmacies, and also provided for free in many public places and businesses, such as hotels, restaurants, and cafes.

The city was busy as we ploughed through the lava-flow of cars and motorbikes in the morning rush hour. By mid-February, Vietnam had been dealing with coronavirus for almost a month, and it was very much in the public consciousness. There had been a handful of cases, but, when my parents arrived, the country was on a clean-streak, during which no new cases were reported for some two weeks. It seemed possible that Vietnam had nipped the virus in the bud.

Life went on. Some travel restrictions were in place, some land borders were closed, temperature checks were common before entering buildings, shops and businesses, and there was a general awareness of the virus – its symptoms, how it spreads, and how to contain it – disseminated largely through public information billboards, banners, announcements and articles. Most notably, each new case since the first domestic patient was announced in late January, was reported in detail on every national news platform. We all knew exactly when and where the latest case was confirmed and the patient’s movements leading up to their testing positive. But, on the surface at least, things were quite normal. Unless you worked in education, as I do, teaching English at a language centre in Saigon. Most public schools had already been closed for weeks, since the end of the Tet Lunar New Year holiday in late January. The language centres, however, hedged their bets, waiting to see how things panned out. The centre where I teach remained open for one week after the Tet holidays, but was now closed indefinitely.

In the taxi, my parents and I headed straight to Bach Dang Pier to catch the mid-morning ferry to Vung Tau, a city by the sea, 90 minutes southeast of Saigon. By now, a high percentage of people were wearing masks in public, both inside or outside. But, despite widespread public information campaigns, not everyone followed the government advice or paid much attention to precautions. Two examples were public gatherings and sneezing.

Vietnam is one of the world’s great drinking and dining cultures. There’s an emphasis on communality and sharing when eating and drinking: the more the merrier. The same is true of other leisure activities, such as going to the beach. In February, large gatherings like these showed little sign of decreasing. Over the last few years, I’ve noticed a kind of sneezing epidemic in Vietnam, especially in urban or industrial centres. I assume this has something to do with deteriorating air quality in Vietnam’s built-up areas (I too have sneezing fits occasionally since moving to Saigon). Whatever the cause, until very recently there appeared to be little etiquette surrounding the sneeze, which was rarely stifled or covered up in public. Manners, of course, differ from culture to culture, and it was only with the rising awareness that a potentially deadly new virus could easily be spread through tiny particles of spittle, that I began to wince every time I heard or saw a sneeze, particularly when no attempt was made to cover it up.

The government advice on masks, however, was generally heeded, even though it was not yet rigorously enforced. At this early stage, the rules were neither strictly imposed by the authorities nor strictly adhered to by the public (myself included). Information was widespread, but official presence was not. As is so often the case in Vietnam, people were largely left to decide for themselves which rules to follow and which to ignore.

At Bach Dang Pier, we bought our tickets to Vung Tau and carried our luggage to the gangway. It was only 10:00am, but the sun was already high and the day was hot. Before boarding the boat, each passenger had their temperature checked. Mum, who’s 75 and had just disembarked from a 13-hour non-stop flight from the UK – taking her from mid-winter in the northern hemisphere to dry season in the tropics, and without having had much sleep – had a slightly high temperature. She was politely asked to step aside and told to wait a few minutes while the other passengers, all of whom were wearing masks, boarded. Mum’s temperature was checked again. Everything was fine. We boarded the ferry and it pulled away from the pier, drifting out onto the thick brown swell of the Saigon River under a blue sky.

*

During the final days of 2019 (before the virus broke in Vietnam) and the first few weeks of 2020 (the early stages of mùa dịch – ‘pandemic season’), I’d been travelling a lot in the southern provinces, camping in particular. From late December until mid-February, I travelled during the short Christmas and Solar New Year break, then the long Tet Lunar New Year holiday, and finally during the initial phase of mùa dịch, a period of unexpected time-off for students, teachers and other workers involved in education, that was essentially treated as an extension of the Tet holiday and became known, briefly among some English teachers in Saigon, as the ‘virus vacation’. (This was, of course, before government advice against non-essential travel, and the onset of travel restrictions and travel bans).

December through March in the southern provinces is ideal camping weather: blue skies and starry nights; dry and sunny in the daytime, cool and fresh at nighttime. I camped in the pine forests of the Central Highlands, along the Cai Valley, by the La Nga River, and I’d seen in the New Year sleeping out on Nui Dinh Mountain in the grounds of a Buddhist temple with a friend, watching the fireworks in Saigon, some 60km away, on the horizon at midnight. We had no idea what 2020 was about to unveil.

Looking back now at December 2019, it feels to me (as I’m sure it does to many people) like a different era: Pre-Covid. The months between then and now have been filled with events very few of us could have predicted or were contemplating prior to January 2020. The things that occupy our thoughts, dictate our lives, our actions, and even form our morality today, were almost completely absent from most people’s minds at the end of 2019. Indeed, even the vocabulary we use on a daily basis now – ‘social distancing’, ‘contact tracing’, ‘lock-down’, ‘Covid’ – had to be learned by most of the world at the dawn of the new decade: the lexicon of a pandemic – a whole new glossary to be absorbed before we could begin to communicate what was happening, let alone understand it or come up with ways to deal with it.

When I look at my Vietnamese language notes from the first months of 2020, it tells the progression of events in single words with their English translations: vi-rút – virus, khẩu trang – mask, thông tin giả – fake news, dịch bệnh – epidemic, cách ly – quarantine, theo dõi người tiếp xúc – contact tracing, gĩan cách xã hội – social distancing, hỗ trợ – support, đại dịch – pandemic, cách ly xã hội – lock-down, mùa dịch – ‘pandemic season’. Most of these Vietnamese words were new to me: in over 10 years of living in Vietnam and trying to study the language, I’d never previously needed to learn them. Now, I saw and heard the words every day. ‘Mask’ was one I had tried to learn in the Pre-Covid era, but it never stuck in my mind. Now, however, I doubt it’ll ever be dislodged from my memory.

Having spent so much of my time during December, January and February outdoors, camping in the countryside and away from major urban centres, I was perhaps less conscious of the escalating situation in China and the wider region than, for example, my friends in Saigon. Although I followed various online news platforms on my laptop and phone, the situation still seemed remote from my personal context. It was only when I returned to Saigon in mid-February, riding in via noticeably muted industrial suburbs, that I began to feel the rising tension of the nation.

The closer I got to the city, the more I could sense the looming fear. When I stopped for gas, an American friend of mine, who’s based in Saigon but was currently on a business trip in the U.K, called to ask my opinion of the situation in Vietnam: should he return there as scheduled, or wait it out in the U.K? I didn’t know how to respond. I was unprepared for the nervousness of the city. I stopped at multiple pharmacies and stores by the roadside on my approach to Saigon in order to buy masks and hand sanitizer. All of them were out of stock.

The next day, I went into my English language centre to teach. Public schools had already closed nationwide, but my centre remained open, albeit with many precautionary measures in place. I enjoy teaching and I’m very fond of my students, all of whom are aged between 6-12 years. The first 10 minutes of each class was a safety announcement presented by the Vietnamese teaching assistant accompanied by a safety video: how to wash your hands properly; how, where and when to wear a mask; how to avoid unnecessary physical contact; how to cover your cough or sneeze with your arm.

Standing in the classroom, listening to the safety talk and video, watching my wide-eyed students – each one of them wearing a mask – absorbing the information, miming the correct handwashing technique, occasionally exclaiming “con sợ” (“I’m scared”), the reality of the situation hit me and I had to choke back tears before I was able to begin teaching my class. The language centre closed the next day. I didn’t teach again until May. For me, mùa dịch had begun in earnest. My parents arrived a few days later.

*

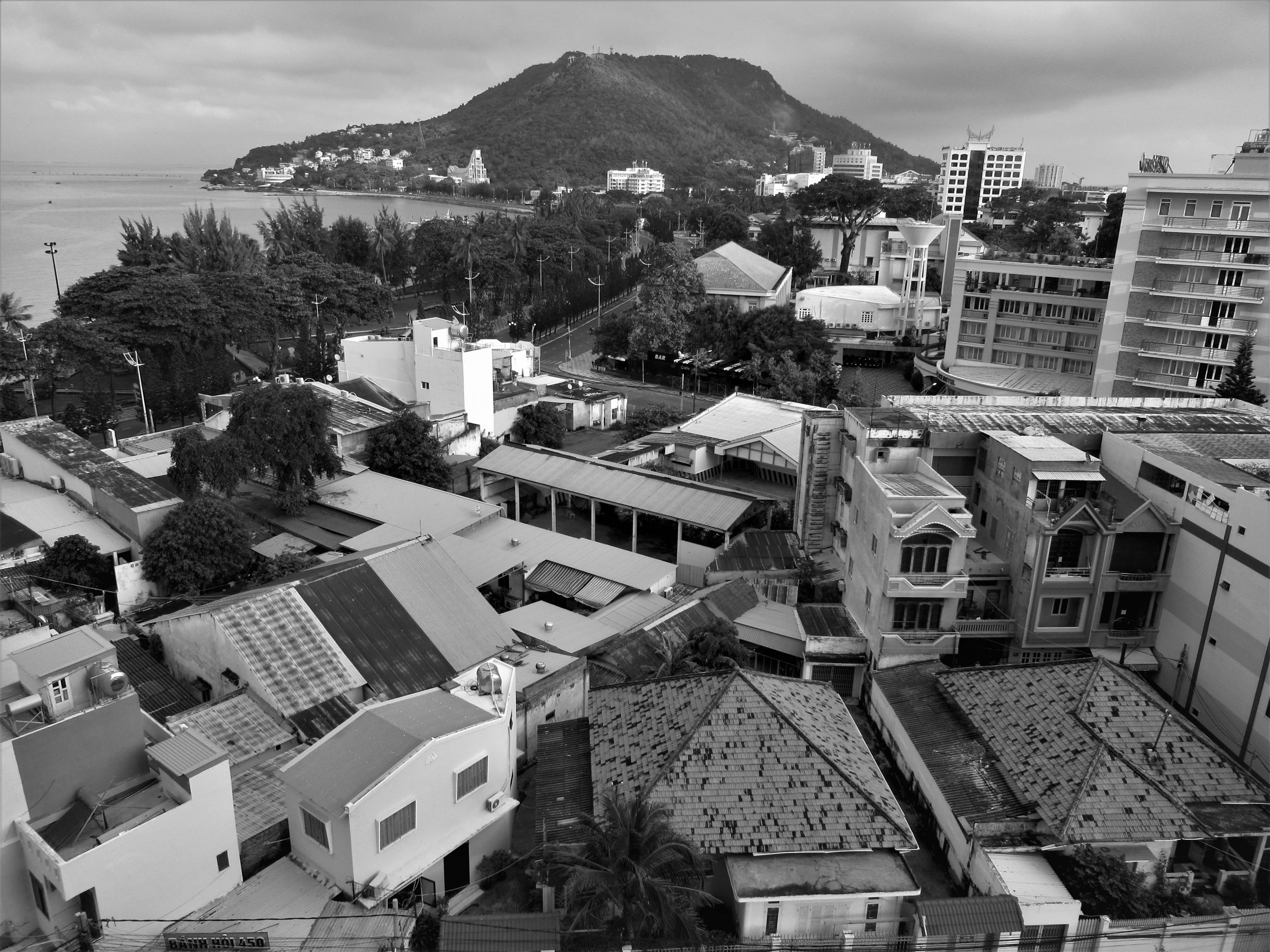

The ferry to Vung Tau sped downstream on the Saigon River, leaving the city behind and dodging giant container ships in its path, until eventually shooting out at the estuary and blazing across a brief section of open sea, before swerving into port. In Vung Tau (currently one of the most pleasant and well-kept cities in Vietnam), my parents were struck by the presence of public noticeboards about the virus. These could be seen on streetsides, in parks, on official buildings, in businesses and cafes. Indeed, there was a large one facing our hotel. These government billboards explained how to prevent contracting and spreading the virus and what to do if you showed any symptoms.

Mum and Dad had come straight from London where, although the virus was by now big news, there was little visible evidence of government action: nothing to reassure citizens that the virus was being taken seriously by the people in charge of the nation. In Vietnam, by contrast, the government-led ‘Covid awareness campaign’ was everywhere and, in most cases, perfectly judged. On the one hand, the notices were highly informative, including contact details for further support or emergencies. On the other hand, they were light-hearted, approachable, and almost child-like and cartoonish in some cases; they weren’t scary, alarmist, or ‘boring’.

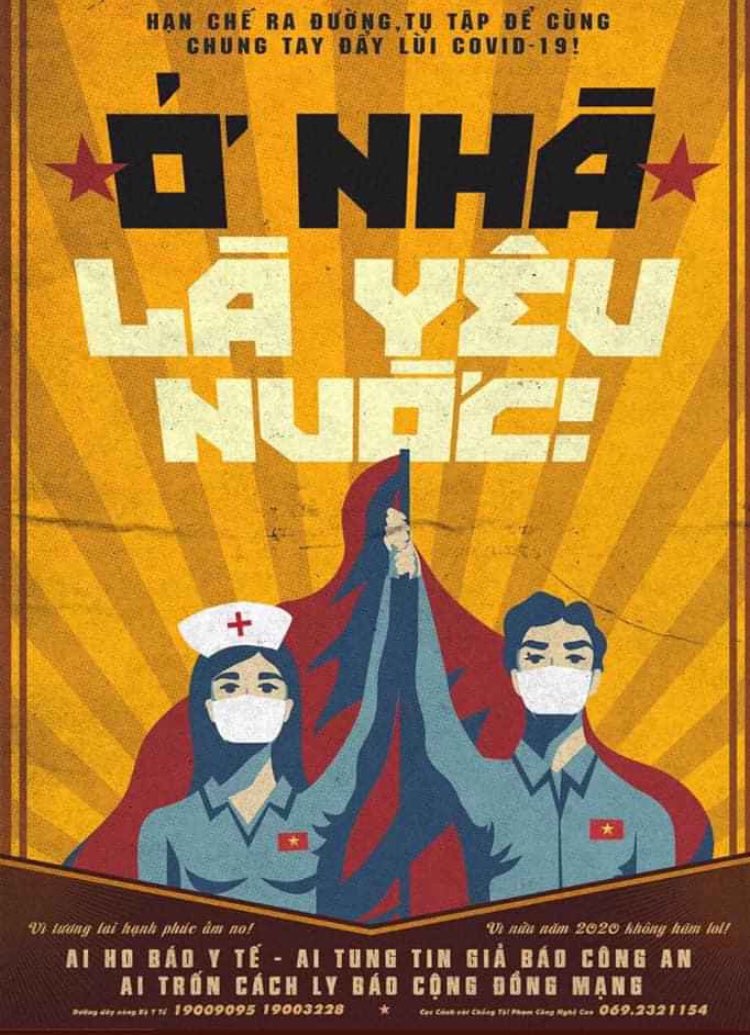

As we explored Vung Tau together – walking the tree-lined backstreets and seafront boulevards – it was impossible not to compare Vietnam’s response to the virus with the U.K’s. Another visually-arresting branch of the government campaign was the invocation of the wartime spirit, which, in Vietnam it would seem, is a part of the national psyche that, although rarely observable in day-to-day life, is nonetheless ever-present just below the surface. In public places, such as squares and parks, stylized, colourful, ‘propaganda-style’ posters exclaimed ‘Let’s fight & defeat the virus together!’ or ‘To stay at home is to love your country!’ This encouraged citizens to associate a sense of national pride with how successfully (or not) the country ‘fought’ the virus.

The awareness campaign also tapped into a deeply cultural sense of social responsibility – especially toward children and the elderly – that I would think has its roots in Confucianism and Buddhism, both of which have played major roles in Vietnamese life and society for two thousand years. Simple, printed banners all over the city drove home the concept that every good citizen should act according to the information at hand, because that was the văn minh (civilized) thing to do.

In Vung Tau, every shop, cafe, or restaurant that my parents and I entered was playing a familiar tune. Now fairly well-known around the world, a government-sponsored Covid song (‘Ghen Cô Vy‘ – ‘Jealous Covid’) was released and went viral. Its catchy melody included many of the messages of the national campaign. But the real genius was in the dance associated with the song that included, among many other dance moves, techniques for washing your hands. Synchronized dancing is a massive youth trend in Vietnam and the wider region, and the ‘Covid dance’ (known as the ‘handwashing dance’ – vũ điệu rửa tay) was perfect for sharing online via TikTok and other social media channels, which meant its reach was astonishing.

*The official Covid song & animation (Ghen Cô Vy):

Watch on YouTube

*One example of many viral performances of the ‘Handwashing Dance’ (vũ điệu rửa tay):

Watch on YouTube

One evening in Vung Tau, as my parents and I were sitting on a balcony with a drink watching the sun set over the sea, I received a text message from the government’s Ministry of Health. Since February, as the virus escalated, everybody residing in Vietnam received these messages on a regular basis. Just like the other public awareness tools, the tone of the messages wasn’t overbearing, overly authoritative, intrusive, patronizing or commanding: this wasn’t Big Brother. Rather, one got the impression of a fatherly figure: benevolent, caring and kind. The information was practical and useful, and the tone was one of collective responsibility and pulling together: keeping yourself safe, of course, but also your fellow citizens.

Included in the messages were quick and easy ways to donate to the nation’s Covid relief efforts, which I and many of my expatriate friends immediately did: it seemed the obvious thing to do. My initial reaction on receiving text messages direct from a branch of government was not one of suspicion (‘How does the government know my number? What about my privacy?’); it was one of gratitude and a sense that the most powerful body in the nation was taking the situation seriously. In all these approaches, the government got the balance and tone just right. This was a subtle, smart, innovative, considered, and intelligent campaign. And, so far, it seemed to be working.

*

As Vietnam’s clean-streak continued, my parents and I relaxed into our time together. We enjoyed Vung Tau for a week or so before moving on, due southwest, to the Mekong Delta. We travelled slowly between several cities on the river’s big, muddy banks, before taking the ferry from Ha Tien, near the Cambodian border, across the sea to Phu Quoc Island, where we were to spend the final days of our trip. Over the course of these weeks, I returned to Saigon on weekends to play tennis matches (my school was still closed, so I had no teaching work) and then rode back out of the city on my motorbike on Sunday evenings to meet up with my parents again.

While I was in Saigon, there was hardly any discernible change in the mood or activity of the city, which was also true of most of the places we visited in the Delta. Although, by Vietnamese standards, the cities were somewhat muffled and operating at perhaps 75% of their usual capacity, nonetheless, shops, restaurants and hotels were open, transportation was operating: everything continued pretty much as normal. But, everywhere we went, people wore masks, people washed their hands with sanitizer and carried it with them about their person, pharmacies were open day and night, and the ‘Covid awareness campaign’ – in all its forms – was a constant presence.

Meanwhile, things were escalating in Europe. Italy was in a bad way and the U.K was beginning to pay the price for its nonchalant approach. It was around this time that my Vietnamese friends started sending me screenshots of social media posts and text messages written by Vietnamese students studying abroad in Europe, who longed to come home to Vietnam and were astonished by Europe’s casual handling of the virus. The messages struck a scared, desperate and despairing tone: people who had gone to doctors in the U.K with Covid symptoms, only to be told to go home and wait it out, then come back in a week if they didn’t get any better; people who wanted to return to Vietnam, but couldn’t afford the air-fare and feared being stuck in a foreign country that was mishandling the pandemic while their own country had it under control. My Vietnamese friends wanted to know: ‘Is this really true? Is this what it’s like in the U.K?’ I didn’t know how to answer.

In Vietnam, this was the beginning of a fundamental change in many people’s attitude, both to the virus (which had previously been seen as a ‘Chinese virus’ but was now shifting in the public consciousness to be seen as a ‘Western virus’) and to the concept of the West in general, which was held in high regard – idolized to a certain extent – for its economic power, standard of living, industrial development and infrastructure. This illusion began to crumble as the virus shifted from east to west, and the latter appeared to mismanage it in a way that was unthinkable to many people in Vietnam. How could a nation sit by as children (still at school is some European countries) and the elderly (the most vulnerable age group and the most deserving of our respect) were exposed to a life-threatening virus? How could this be allowed to happen, especially in countries as wealthy and ‘developed’ as those in Western Europe? How could a government, a nation accept this?

In Vietnam, the reaction to the unfolding catastrophe in Europe was, at first, quiet disbelief. But soon it threatened to become anger and outrage, as events transpired that led many in Vietnam to view the negligence and lack of discipline in Europe as a direct threat to the health and security of the Vietnamese people. Vietnam was about to experience its second wave (although the first had hardly been more than a trickle), and it arrived by plane from Europe.

*

Vietnam’s clean-streak ended as a slew of international arrivals on flights, usually from Europe, entered the country and later tested positive for the virus. These new cases had apparently arrived in Vietnam without having undergone any testing from their points of departure: no temperature checks before boarding the plane, no wearing of masks in terminals or onboard aircraft; passengers weren’t even asked if they displayed any symptoms prior to travel. This burst the bubble and it seemed the cases were now bound to grow exponentially in Vietnam, as each day new patients were announced and the country’s fear became tangible. In particular, a fear of foreign tourists, because who knew whether they had flown into Vietnam on one of the ‘Covid flights’? Who knew if they had been taking the necessary precautions that people in Vietnam had already been doing for two months? Who knew if they had arrived from a country, such as the U.K, where the government didn’t appear to be on top of the situation?

For my parents and I, enjoying a comfortable stay at Bamboo Cottages on Phu Quoc Island (which still had no confirmed Covid cases), this made the last week together one of growing concern and nervousness. It started to become clear that, at some point, Vietnam (and possibly the rest of the world) would have to close its borders and cease all international flights. My parents, both in their mid-seventies, needed to make a decision that would essentially determine where they would be during what would become known as ‘lock-down’.

There were two options available to my parents: change their return flight and stay in limbo in Vietnam, so far with a good Covid record but currently in the grip of a flare-up (not to mention the financial extras this would entail, and the uncertainty of visa renewals and if/when they’d be able to get back home again); or return to the U.K on their scheduled flight, where the situation was already out of control and cases far outnumbered those in Vietnam, but where they had access to a house in the countryside, hospitals and medical treatment on the NHS (National Health Service).

The last few days of my parents’ visits are always difficult, because of the looming prospect of another goodbye. On this occasion, the uncertainty of whether they would stay in Vietnam or return to the U.K and the current instability of most of Europe, made it all the more tense. After days of emails and phone calls, Mum and Dad decided to keep their return flight to London as the cost of changing their tickets was too high to justify. As it turned out, my parents’ flight back to the U.K was just a week before all international flights in and out of the country ceased and Vietnam effectively became a nation in isolation.

We spent the last day or two alternately trying not to contemplate the journey too much while also devising protective strategies for the flight. Even in normal circumstances, air-travel – especially long-haul – is a catalyst for catching illness. What’s more, almost all the new cases in Vietnam over the past week were unsuspecting passengers cooped up in airline cabins for hours, breathing recirculated air with an unknown Covid patient onboard. We read-up on the advice online, such as how to disinfect an airline seat and video screen, and how to effectively use a mask and hand sanitizer.

My parents left our resort on Phu Quoc Island on a lovely evening, as the sun was setting over the Gulf of Thailand. They were on a flight back to Saigon, and then direct to London. I walked them to the minivan that would take them to the airport. We said goodbye. But I found it difficult to look my parents in the eyes. None of us knew when it would be possible to see each other again. We still don’t. No one does.

*

I left the island the next day. Back on the mainland, in Ha Tien, everything had changed since I was last there, less than two weeks earlier. It was quiet. Tense. Hotels were open but empty. Markets, shops and cafes were doing business. The boats were running. But there was a stillness – unheard of in most typical Vietnamese towns and cities, which usually throb with activity and commerce. Noticing a change in mood, I started to document my street food meals, sensing that this daily pleasure – affordable, ubiquitous, life-affirming and full of colour – might not be available much longer if a lock-down was to be enforced, which now seemed increasingly likely.

The next morning, a new Covid case was announced in the online news sites: a foreign man on Phu Quoc, who’d been on the island for a week during the same time my parents and I were there. Fortunately, because the government’s contact tracing was so thorough and the details made public immediately, I was able to read about the man’s movements on the island – where he stayed, where he ate, where he travelled, whom he came in contact with – and deduce from this information that neither I nor my parents were ever in proximity to him, having stayed in, and travelled to, completely different parts of Phu Quoc. Nonetheless, this was as close as I’d been to a reported case of the virus.

I felt I had to return to Saigon before lock-down was announced. I rode my motorbike down narrow paved lanes and dirt roads, and along dykes above irrigation channels bisecting an endless patchwork of rice fields, between Ha Tien and Can Tho. I heard from my parents, who’d arrived safely back in London and were now planning to leave the city as soon as they could for the countryside in Wales, because they too were anticipating a lock-down and preferred not to be in London for it. From Can Tho, I continued on back-roads, interrupted by several ferries across branches of the Mekong River, to Saigon. The moment I re-entered the city, for the first time in three weeks, I knew that this was not the place I wanted to spend lock-down.

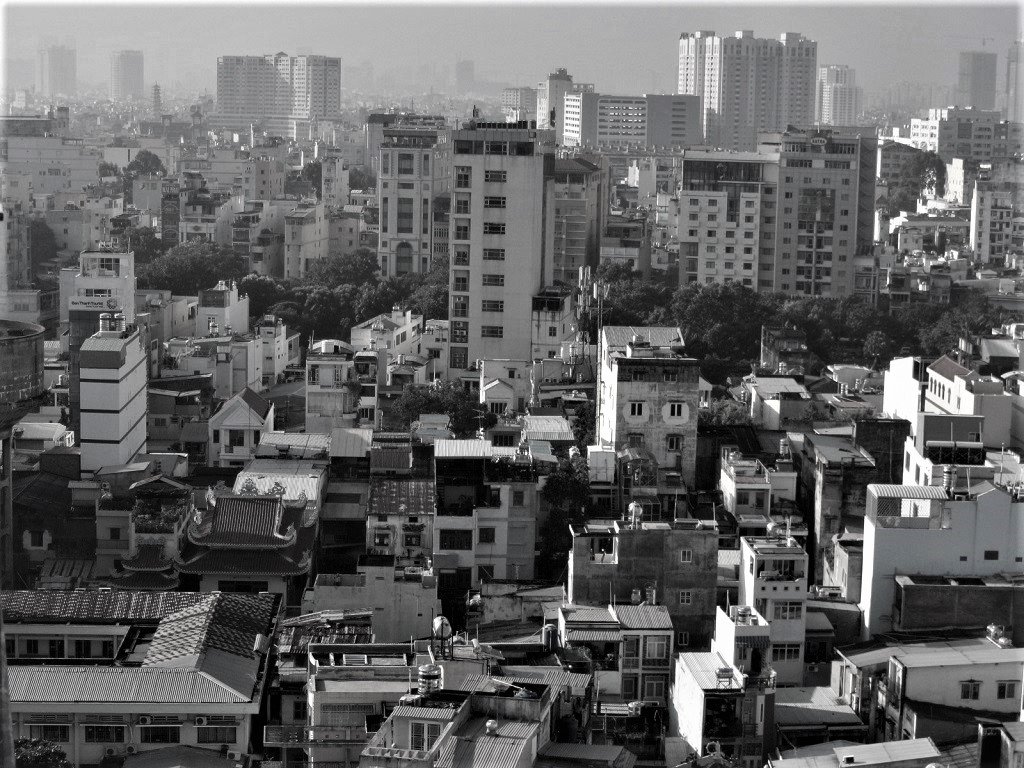

Saigon appeared ghastly to me: choked with exhaust fumes, dirt, traffic, and people. If the virus was going to take hold anywhere, I felt, it was here. I’d been lucky enough to have spent the previous weeks in quieter, greener, cleaner, more rural parts of the country, and in the time since I was last in Saigon, there had been a lot more talk about physical distancing and self-isolation. Surely this was a hopeless concept in a place like Saigon. Even in my own home, which I share with three friends, it was ludicrous to contemplate physical distancing in an enclosed house with four tenants in the middle of a city of 8 million people. Saigon had already reported individual cases and clusters since the second wave had hit. Whole neighbourhoods and entire apartment blocks were quarantined. There was a sense that the virus was closing in.

The next morning, I paid my landlady three months rent in advance and rode out of the city again, this time with my tent, full camping gear, and food supplies. This may seem paranoid and absurd now, but at that time we really didn’t know what was going to happen in Vietnam, or the rest of the world for that matter: would lock-down commence? how strict would it be? how long would it last? would food run out? would looting take place? would the virus spread throughout Vietnam? would hospitals become overrun? No one knew. I only knew that I wanted to be anywhere but Saigon. As much as I love the city, it’s not the place I wanted to wait out a pandemic of unknown proportions.

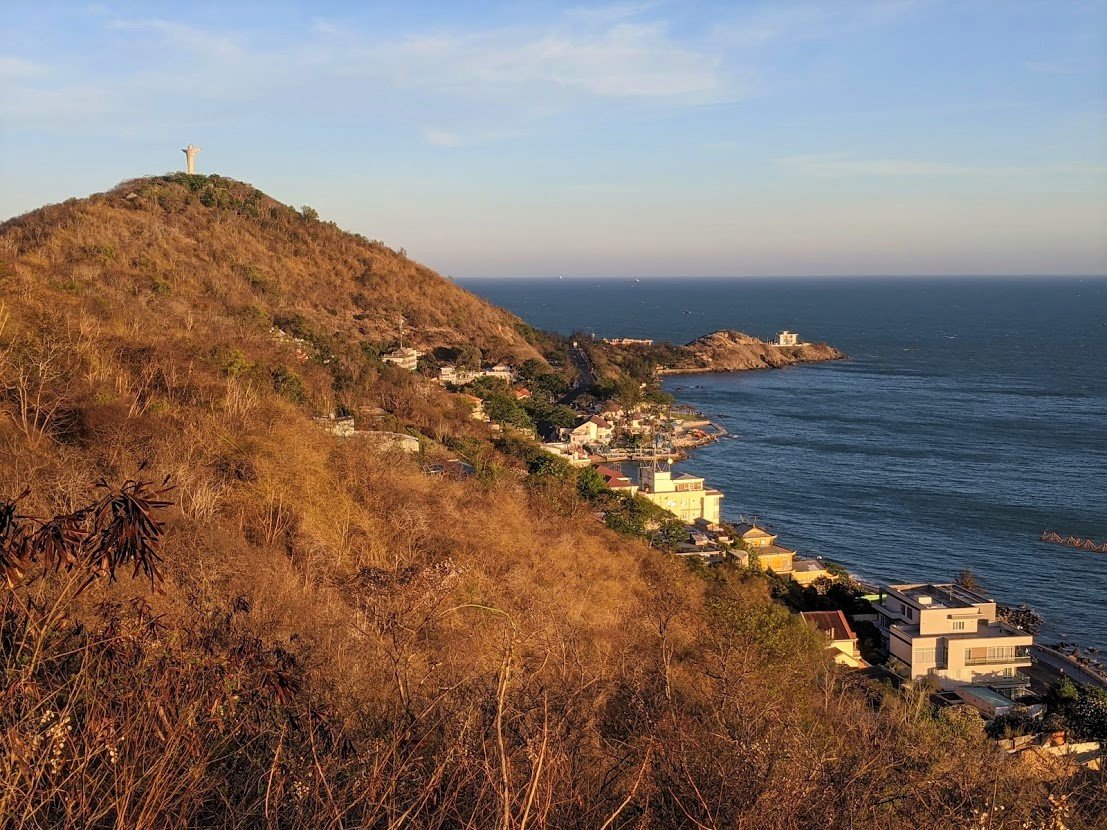

I headed, initially, for Vung Tau, where I knew there was, at least, the ocean, the hills, the horizon, cleaner air, no reported Covid cases, and easy access to empty stretches of coastline or sparsely populated highlands: the kinds of places that one could effectively practice physical distancing and self-isolation. For me, this turned out to be a good move.

PART 2: Lock-Down

*IMPORTANT NOTE: Part 2, including the introduction below, was written and published in November 2020, six months before the outbreak of Vietnam’s fourth (and worst) wave of the pandemic.

Introduction to Part 2: While writing the second part of this ‘Covid trilogy’, a third wave of the virus hit Vietnam. The outbreak began in Danang in late July and was contained by September 2nd, since when there hasn’t been a single reported community transmission. During that month, the total number of cases nationwide doubled (the tally currently stands at 1,304), and Vietnam went from zero fatalities to 35. A citywide lock-down was imposed on Danang, but most of the rest of the nation remained open and did not experience a second lock-down. Thus, Vietnam still only had one nationwide lock-down during the pandemic, which took place in April, 2020. And that is the period of time which part 2 of this ‘Covid trilogy’ focuses on.

Although part 2 is intended to be read as one continuous narrative, I recognize it’s a long piece and many people won’t have time to read it all. Therefore, I’ve broken the narrative into convenient mini-chapters. (For further context, please read the introduction to this ‘Covid trilogy’ and my Disclaimer statement.)

- Decision Time

- Invisible Threat

- Vung Tau: Pandemic Retreat

- Implementation & Enforcement

- Lock-Down Lifestyle

- Face Masks: Culture & Etiquette

- Psychology of Lock-Down

- The ‘Fight’

- Taking ‘Action’

- Resistance & Compliance

- Pathos & Poignancy

- Human Warmth & Social Life

- A Moment of Hostility

- Impacts on the Environment

- Easing Restrictions

- Success & Recognition

- Last Days of Lock-Down

*

MAP: Part 2: Lock-Down

*

[Back]

*

Decision Time:

Three hours after leaving Saigon on my motorbike on a hot, clear, dry season morning, I arrived in Vung Tau. I’d taken the longer, scenic route: partly to avoid horrible roads, but partly so as not to draw attention to myself. The government had advised against non-essential domestic travel, and foreign travellers were increasingly seen as a health risk. International air routes were still open and the West was now at the centre of the pandemic: many people in Vietnam were understandably nervous about being in close proximity to Westerners, whom, for all they knew, might have been recent arrivals from Europe or the United States, where the virus was already out of control. What’s more, I was conspicuous as a foreign man with a guitar on his back whose motorbike was loaded with gear.

It was mid-March. Social- and physical-distancing restrictions were already in place across the nation, pockets of infections were flaring up here and there, and a nationwide lock-down was imminent, but nobody knew exactly when it would begin. I’d left Saigon to avoid spending lock-down in a congested city of 10 million people. My first stop was to be the seaside city of Vung Tau, from where I’d likely continue along the coast and up into the mountains. I intended to spend the next few weeks – or however long lock-down lasted – on the road, moving from one isolated place in the Vietnamese countryside to another with my tent. This was to be my way of social- and physical-distancing: staying away from urban centres, limiting my personal interactions, keeping safe, and waiting out the pandemic.

Now that we’re almost a year-deep into the pandemic, it’s easy to forget just how unsettling the prospect of lock-down was. Today, lock-down is associated with frustration and boredom; but in the first quarter of 2020, when lock-downs began to be announced across the world, there was a tangible nervousness in the air and a sense of fear among the public. On my motorbike, I had brought a tent, camping equipment, canned and non-perishable food supplies, and three separate stashes of cash hidden in my luggage. I was prepared for a long period of self-isolation: on the road, in the countryside, camping in the mountains and in the forests. This might seem excessive and paranoid in hindsight, but, months later, when lock-down was over, businesses reopened and we began to go out and socialize freely again, I met several other people who confided in me that they too had made similar preparations to mine back in mid-March.

Riding into Vung Tau on the wide, breezy seafront road, the city was empty. It was a Monday. Vung Tau is a weekend economy: from Friday evening until Sunday afternoon the hotels, beaches, bars and brothels open for business and the punters pour in from Saigon and the surrounding region to let their hair down. But, during the week, the city is quiet, tidy, handsome, neat and attractive. I rolled into town in the early afternoon, the waves crashing on the embankment, tankers, freighters and oil rigs on the horizon. I checked into an empty hotel within sight of Bãi Trước (Front Beach).

At that time, I was receiving emails from readers of this website from across the nation who were reporting that some hotels and guest houses were refusing to accept foreign guests. (This was subsequently directly addressed by Vietnam’s prime minister, Nguyễn Xuân Phúc, who issued a statement that hotel owners were required by law to accept foreign guests, unless they’d been informed otherwise by local authorities.) When I arrived in Vung Tau, however, I immediately found a hotel that accepted me and planned to remain open for as long as possible. What’s more, the hotel was willing to offer me a discounted rate for a long-term stay.

Vung Tau felt good: safe, comfortable, convenient, clean and spacious, with easy access to nature in the form of the ocean, the hills, the windy seafront boulevard, and the peaceful hillside pagodas. The city had all the basic necessities I required and quite a few comforts, too. There were cafes, lots of food and drink options, shops, hospitals, and a couple of ‘Western stores’ where I could buy things like British-style pies and French cheese. Each day that I stayed in Vung Tau, news of infections across the nation got worse, restrictions became more serious, lock-down grew nearer, and I became more nervous and uncertain about my plan to stay on the road and camp. If I moved on from Vung Tau and lock-down was suddenly announced, I might get stuck somewhere else – a different town or city that wasn’t as favourable as Vung Tau or where I couldn’t find accommodation. If I was going to be stuck anywhere, I wanted it to be Vung Tau. After several days in the city, I abandoned my plan to camp and decided to stay in Vung Tau for as long as social- and physical-distancing and the impending lock-down lasted.

My period of self-isolation and lock-down lasted some six weeks, all of it in Vung Tau. This was the longest stretch of time I’d spent in one place for as far back as I can remember.

[Back]

*

Invisible Threat:

Over the course of 2020, for many countries around the world, lock-down has become a way of life: a ‘new normal’. This is particularly true of those nations in the West that failed to act early enough or decisively enough when the virus first broke, such as the UK and the United States. In Vietnam, however, lock-down was only a momentary pause – a brief ‘circuit-breaker’ – before normal life could continue pretty much as before. But, back in the first quarter of the year, no one knew how effective lock-down in Vietnam would be in containing the virus, nor whether further lock-downs would be required.

With the exception of a few particularly hard-hit enclaves, nationwide lock-down in Vietnam only lasted for 2-3 weeks, beginning on April 1st, 2020. Indeed, when talking to my Vietnamese friends, many of them stress that even those weeks weren’t really considered a ‘lock-down’ as such: rather they were viewed as a period of severe social- and physical-distancing. By contrast, my parents in the U.K and my friends scattered across the world – from Barcelona to Costa Rica to California – endured (and, in some cases, are still enduring) several months of lock-down.

By the time I arrived in Vung Tau, the coronavirus dominated people’s daily lives around the world. The virus dictated many of our actions: where we worked (if we worked), what we worked on, who we saw, how we interacted with them, what we talked about, and what we thought about. And yet, the virus was still essentially abstract for most people, especially in Vietnam, which had so few recorded cases. At that time, everyone I knew had been affected by the virus, but no one I knew had been infected by the virus. Covid-19 was the main news item on every media platform, but it wasn’t yet a personal reality. All our lives had been turned upside down in a matter of weeks by the threat of something we couldn’t see. This made it a slightly surreal – but no less unnerving – situation.

In Vietnam, however, I rarely came across anyone who didn’t believe in Covid-19 or thought it was all a huge conspiracy. Meanwhile, in parts of the US and Europe, there appeared to be some skepticism associated with the virus, as well as a certain resistance to rules and regulations imposed to contain its spread. Cultural differences aside, this reaction is surely due in part simply to the non-visible nature of the virus. People weren’t immediately falling sick on the sidewalks, gasping for breath in public places, convulsing in the streets, or transforming into zombies in front of our eyes. If Covid-19 had manifested itself in, say, a cloud of purple vapour issuing for the nose and mouth of anyone who carried it, we’d all be better able to comprehend the reality of the virus and its threat. Indeed, we’d all be more serious about implementing preventative measures: we’d carry out social- and physical-distancing with more diligence, we’d be more conscientious about obeying lock-down regulations, and we’d all wear masks.

Imagine walking a street in London, Paris, New York or Ho Chi Minh City when suddenly a puff of purple vapour wafts over from an unmasked pedestrian, signalling clear evidence of your proximity to a new and potentially deadly virus: everyone on that sidewalk would mask-up, bolt in the opposite direction, report the Covid-carrying pedestrian to the authorities, go home, stay home, lock-down, and self-isolate without any questions or conspiracy theories.

But, invisible or not, the virus inevitably closed-in on my personal experience (as I’m sure it did for many people). In Vietnam, some of my friends were quarantined for many weeks. And, by the middle of the year, two of my friends’ parents had passed away from Covid-19: one in the UK and one in the United States, both countries which had failed to act seriously when the virus first spread to their borders, and both countries that had remained resistant to mask-wearing, self-isolation, quarantine, contact-tracing and myriad other regulations and actions that the Vietnamese government and people had taken early on in the pandemic.

[Back]

*

Vung Tau: Pandemic Retreat

Vung Tau is a peninsula poking southwest into the East Sea, near the mouth of the Saigon River. Only a hundred kilometres from Saigon and reachable by road in just 2 hours (or even less by fast boat ferry), Vung Tau has long been a popular weekend escape for city dwellers. But, when I first got to know it, between 2005-2010, Vung Tau was a trashy, noisy, crowded, and polluted tourist town with a seedy underbelly and a boozy expat scene. There was a sense of vice about the place, which I’d rarely felt in other Vietnamese towns. In the last few years, however, the city has transformed itself and cleaned up its image. Vung Tau is now an attractive, well-organized, increasingly affluent and ‘respectable’ seaside city. This was my home for some 50 days during the height of Pandemic Season in Vietnam.

In normal times, I travel a lot (but almost always within Vietnam’s borders) to research and write the guides, reviews and articles on this website. My general rhythm for the last few years has been to spend one week in Saigon (where I’m based) and the next week on the road. However, no matter where I travel during the week, I always return to Saigon for the weekend, in order to teach my English classes on Saturday and Sunday. Sometimes this requires riding through the night on my motorbike; other times, I take night trains or sleeper buses from anywhere in the country that arrive into Saigon before dawn on Saturday, giving me enough time to shower and have breakfast before my first class begins at 7:40am. I rarely fly: partly due to a rapidly growing sense of flygskam, but also a creeping fear of flying that began in my late twenties. My lifestyle being such, I can’t remember the last time I spent more than two or three weeks in one place. Lock-down and self-isolation changed that: Vung Tau marked the longest number of consecutive days and weeks I’ve spent in one place for several years.

Like many coastal cities in Vietnam, Vung Tau is on the up-and-up. The city’s accommodation – from hotels and homestays to budget hostels and Airbnbs – gets better every year; its beaches are cleaner and the water quality clearer than at any other time since I’ve known it; street food is thriving and local seafood is fresh and delicious. On the hillsides, there are still some attractive century-old french-colonial villas, and, dotting the city streets, interesting examples of Vietnamese Modernist architecture. People are friendly and noticeably healthy and active: the long, attractive seafront road with wide, well-maintained sidewalks is used every morning and evening by locals of all ages for promenading, cycling, running, dancing, calisthenics, football, and swimming in the ocean. There’s an active cafe and bar scene, and, although the seediness still exists in the dozens of euphemistically named ‘massage’ parlours and ‘karaoke’ bars, these feel like relics of the past: old neighbourhoods awaiting demolition.

In Vietnam, lock-down was the point at which most people finally acknowledged that the virus wasn’t just going to go away, pass us by, or leave anybody unaffected. As soon as lock-down came into effect, there was an almost instant nostalgia for the pre-Covid era: when borders were open, travel was possible, going out for street food or to bars with friends – or going out at all without a mask – was acceptable. Even the simple act or thought process of making plans for the future wasn’t possible. The future was no longer a graspable concept: not something predictable enough or stable enough to plan for. One had no choice but to take things as they came, one step at a time: remain adaptable, don’t make plans, don’t look too far ahead, and don’t dwell too much on the past. Staying present was the only thing to do, because the present was all that seemed to exist during lock-down: the rest was uncertainty.

Even so, my own physical and social context during lock-down in Vung Tau was comfortable, secure, and relatively free. I attribute this largely to the city itself, which I grew very fond of. But, I was also lucky to have my two friends, Ben and Ruby (and their dog, a Miniature Pinscher-Chihuahua named ‘Sushi’), for company. They too had fled Saigon for Vung Tau and rented an Airbnb apartment for the duration of lock-down.

Many of Vung Tau’s streets are wide, leafy, and handsome. The thick, grey, gnarly trunks of century-old trees lining the french colonial-era grid of streets behind Bãi Trước beach (whose roots run beneath the road surface, rupturing the smooth asphalt), look like elephant’s feet astride the boulevards. The ocean stretches to the horizon, criss-crossed day and night by shipping of all sizes: tankers, container ships, wooden fishing vessels, coast guards, rescue boats, and fast ferries to Saigon and the Con Dao Islands. On the horizon, a constant line of cargo ships in silhouette, with plumes of smoke billowing from their funnels streaking the sky in the direction of the prevailing wind, like vaporous windsocks. The seafront road wraps around the entire peninsula, offering views out across the bay and back to the marshlands, mangroves, shipping ports and factories due west toward the mouth of the Saigon River.

The city is large but manageable, most of it nestled on the flat land between the peninsula’s two peaks, Núi Nhỏ (Small Mountain) and Núi Lớn (Big Mountain), both of which are covered in flowering tropical trees. The lower slopes are scattered with villas, hotels, and leafy Buddhist pagodas, all connected via steep, narrow paved lanes, like a medieval village rising up from the harbour on a Mediterranean island. On both ‘Big’ and ‘Small’ mountains, several lanes continue up past the villas and pagodas all the way to the peaks, snaking through hairpin bends, past military outposts – some abandoned, some operational – before summiting and revealing expansive views over the city and out to sea.

In the course of just a couple of months, everything had changed. Hobbies, sports, social life, professional life, family life – all of it was on hold and in a kind of limbo. In my own professional life, I have two means of income: I teach English and I run this website. My language centre in Saigon initially closed in February, but was quick to transition to online classes once lock-down began in April. However, I wasn’t able teach online as the internet connection where I was staying in Vung Tau wasn’t strong enough or reliable enough. Understandably, my school didn’t want online classes to be disrupted by lost connections and slow loading.

My website immediately suffered. The site traffic went off a cliff, beginning in February and progressing through March and April. By that time, no one was travelling in Vietnam nor was anyone making plans to travel to Vietnam in the future. Although it was hard to see the momentum of my website – which I’ve built-up over almost a decade – crash so suddenly, so unexpectedly and so dramatically, it wasn’t difficult to accept this consequence of the pandemic and to see it in the larger, extremely fortunate, context I was in, especially compared to most people in Vietnam, or for that matter, the world. I was in Vung Tau: I was comfortable and I was safe.

Vung Tau has one, long, sandy beach stretching along the east of the peninsula, known as Bãi Sau (Back Beach). This is where most of the high-rise hotel chains, nightclubs, souvenir shops, convenience stores, and vacation paraphernalia are: the touristy side of the city, without much charm or character, but with lots of sand and surf. Beyond Bãi Sau, rounding the southern tip of the peninsula, a giant statue of Christ looms over the city, gazing out to sea with arms aloft as though contemplating flight. Christ sits atop one of the lower peaks of Small Mountain, whose rugged slopes fall to the ocean creating Bãi Dứa (Pineapple Beach), a blustery but attractive and mesmerizing section along the seafront road with several good hotels, apartments, villas, and pagodas. From here, the embankment road swings north, stretching beneath the green heights of Small Mountain with its white, French colonial-era lighthouse placed on top like a cake decoration. Next, Bãi Trước (Front Beach) comes into view, a gentle, curving bay backed by a palm-studded seafront park with a hem of sand exposed at low tide and a clutch of wooden fishing boats moored offshore. Still, to some extent, a local beach, Bãi Trước is classy, characterful, and charming: well-used by local people of all ages, as well as vacationers.

North of Bãi Trước, the steep slopes of Big Mountain bear down on the city, meeting the ocean at Ho May Port, where the boats arrive and depart for Saigon, and a cable car slides up the hillside to a theme park on the flat summit of the mountain. The white walls of Bach Dinh Palace, the former French Governor’s residence, stand out from the trees on the lower slopes. Continuing around the bottom of Big Mountain towards Bãi Dâu (Strawberry Beach), it feels increasingly like the affluent suburbs of Vung Tau, with sea-view apartments hugging the bay and modern villas hiding in the brush on the hillside, along with several Buddhist monasteries, temples, shrines, and a colossal statue of the Virgin Mary. Further still, to the northern tip of the peninsula, the seafront road turns back on itself, entering the rougher world of Ben Da fishing port and market. Well in the shadow of Big Mountain, a large fishing fleet shelters in a wide, calm inlet surrounded by fish processing-and-packaging factories and an oil rig depot. From here, a concealed lane heads up along the spine of Big Mountain, passing a French colonial-era cannon fort, and climbing to giddy heights with panoramic views.

All things considered, I was very lucky: there was a lot to do and a lot to keep me busy; a lot to keep my spirits high and a lot to be grateful for and happy about. This was especially true as it became clear that Vietnam was a fortress against the virus compared to many countries around the world. I was lucky to be in Vietnam, but I was particularly lucky to be in Vung Tau, where (to the best of my knowledge at the time) not a single case of Covid-19 had been recorded, and where I had almost everything I could hope for. Sometimes, when Ben, Ruby, ‘Sushi’ and I would meet-up and walk along the empty seafront road or ride up to a viewpoint on the slopes of Small Mountain, all we could do was marvel at how fortunate we were to be in Vietnam, and how attractive and safe Vung Tau felt. It was difficult to believe what was going on in other countries, such as my own, the U.K, or Ben’s, the U.S.A. From where we were sitting, things appeared serene, safe, and under control.

[Back]

*

Implementation & Enforcement:

Nationwide lock-down in Vietnam began on April 1st, 2020. In addition, the weeks leading up to lock-down were considered a period of heightened social- and physical-distancing, during which many activities were either discouraged or banned outright. This, like so many rules and regulations in Vietnam, was essentially a ‘soft-opening’ for the inevitable lock-down that would succeed it: In the weeks prior to lock-down, the population was introduced to the idea of a lock-down and what that would entail, which took the form of heightened social- and physical-distancing. Indeed, during this period, many of the lock-down regulations were already in place, but, in reality, they weren’t generally adhered to. Rather, in March these restrictions were treated as suggestions, until, finally, from April 1st, they became rules that must be obeyed and taken seriously, and would be strictly enforced by authorities. Those not following the rules would be held to account: through verbal warnings, on-the-spot fines, and even detention.

In Vung Tau, an example of the ‘soft-opening’ principle could be seen in the local authorities’ attitude toward public gatherings at the beach. My hotel was a short walk from Bãi Trước (Front Beach). Before lock-down began, there were clear and obvious signs all along the seafront stating: ‘No Bathing and No Gathering in Large Groups at the Beach’. And yet, every evening from 4pm, crowds of locals and some visitors (including myself and my friends, Ben and Ruby) flocked to the seafront park to play around, promenade, and bathe in the ocean as the sun set on the horizon out at sea. Hundreds – perhaps thousands – of people each day frolicked in the waves, picnicked in the seafront park, and showered together in the public cubicles on the walkway. But, on April 1st, when everyone showed up as usual to Bãi Trước beach at 4pm, the rules were enforced. Uniformed authorities prevented anyone from entering the waterfront park, or from walking along the promenade, or from swimming in the sea, or from using the public showers, or from kicking a football along the pavement. Everyone who showed up was simply turned away: politely but firmly told that it wasn’t possible to hang out and enjoy Bãi Trước beach anymore. A public address system on the back of a truck reinforced the message, playing a recording on a loop stating the rules of lock-down and the fines that would be imposed on those breaking them.

But, even then, official presence consisted of barely a dozen uniformed men and women patrolling the seafront. This handful of unequipped (save for an occasional baton) officials were in charge of controlling crowds in the hundreds. Presumably, the crowds were very disappointed not to be able to go to the beach anymore (as, indeed, were my friends and I), but there were no public displays of anger; no bemoaning the new enforcement of rules that, ultimately, we all saw the logic in; no protests or confrontations with authorities. We all just went home and worked out other ways to unwind in the evenings that didn’t involve going to a crowded beach during a pandemic. For the majority of my time in Vung Tau, I didn’t feel oppressed by the government’s lock-down regulations, I didn’t feel my independence and freedom were threatened by the physical-distancing laws, and I wasn’t suspicious or resentful of them. And, as far as I could tell, nor was anyone else I knew in Vietnam. We all saw the benefit and necessity of the rules and regulations: admittedly, not enough to follow them before lock-down – in the ‘soft-opening’ period – but certainly enough to obey them once lock-down finally came into effect.

Crucial to the public’s compliance with lock-down regulations, however, was the success the Vietnamese government had already had in containing the spread of the virus: they’d proved their approach was effective, and this made us (the populace) trust their regulations and follow them. This, of course, was not the case in my own country, the UK, nor in the US, nor many other nations in the much wealthier West. Governments there had failed to act early enough or decisively enough. And, by the time they were finally taking the pandemic seriously, it was already too late: public trust in their government had diminished and the citizenry was so divided that no lock-down strategy could be effectively enforced.

[Back]

*

Life in Lock-Down:

As it dawned on me that I would be in Vung Tau for an indefinite period of time (at least as long as lock-down lasted), I began to set up my hotel room as though it were an apartment and treated it like a temporary home. I bought some basic food supplies and a few large plastic barrels of drinking water and squared away one corner of the room for snack-, coffee-, and tea-making. In another corner, by the window, I set up an office space for working on my website and writing emails. Another corner – on a soft chair with a low desk – I allocated as my social-life and recreational space: for Skype calls, watching movies, playing the guitar, reading, and exercise.

Gradually, a daily rhythm set in. I got up at a reasonable hour (not particularly early, but not too late), practiced a breathing technique for 15 minutes on the floor of my room, and did some stretching. Then, I took a shower and made coffee and breakfast in my room: muesli, yogurt, nuts, honey, and a banana. I read the news online, attended to emails, and did some writing on my website, then I went for a swim. Mid-morning, I’d walk or ride my motorbike to get a fresh orange juice to take away in my flask at the juice store on the corner of Le Lai and Pham Ngu Lao streets, and pick up another coffee at one of several cafes that remained open (take-out only, of course). Sometimes I’d have a second breakfast, such as bò kho (beef stew) at Duyên soup house or pick up some baked goods at Bánh Mì Thi Thi. Then I’d ride my motorbike to the seafront, or to one of several hillside pagodas on the slopes of ‘Big’ and ‘Small’ mountains, or to a bench beneath a bodhi tree on Thong Nhat Street. (The latter I’d often be sharing with a local ‘tramp’, sprawled out, semi-conscious, in a drunken sleep, the two of us causing any passersby to do a double take: we must have looked an odd couple). At any of these places, I’d spend an hour or two nursing my second coffee of the day while writing and working on my website, or just thinking, taking in the views, and absorbing the eerie peace of lock-down.

Mid-afternoon I’d head back to the town centre to fill my flask with rau má juice (a clover-like green leaf with a vegetal flavour served over ice, often translated ‘pennywort’ or ‘centella’) from Bà Già, a long-running Vung Tau institution famous for its juices, which remained open throughout the pandemic. Next, I’d buy some food to take back to my hotel room for dinner later in the evening: sometimes I’d fill my reusable box with an assortment of vegetarian dishes from a little, friendly place on Le Lai Street, or rotisserie chicken from either Léo or ‘chicken corner’, or English-style pies, cheese, biscuits and dark chocolate (a treat) from one of the few ‘Western stores’ in Vung Tau, such as Linh Phuong and Q-MART, catering to the tastes and needs of the expat community. Before returning to my hotel, I’d stop to drink a fresh coconut at a roadside shack.

The late afternoons I spent exercising. Sometimes I’d run along the seafront road, or go for another swim, or do HIIT (high-intensity interval training) routines in my room, or stretching and yoga outside on the patio. I tried to vary my exercise each day. The evenings were my social and leisure time: a Skype call with a friend or family member somewhere in the world, or even a real-life, in-person meet-up with Ben, Ruby and ‘Sushi’. We’d go for a stroll and a chat, or a movie at their place with a take-out pizza from Pizza Leo, or a home-cooked meal which Ben and Ruby were kind enough to produce. Finally, my nights consisted of another 15-minute breathing session, some songs on my guitar, a hot bath accompanied by my Kindle and a ginger tea, then a movie or a couple of episodes of a series or a comedy on my laptop to put me to sleep.

[Back]

*

Face Masks: Culture & Etiquette

When lock-down began, on April 1st, all the rules and regulations surrounding social- and physical-distancing and self-isolation that had been lightly upheld during the ‘soft opening’ period, were now fairly strictly enforced. Of all these rules, wearing a face mask was the most commonly adhered to, even as far back as late January, when the virus first broke in Vietnam. As has been repeatedly pointed out in Western media, the transition to wearing face masks in public may have been easier in East Asian and Southeast Asian countries because, in this part of the world, many millions of people have been wearing masks to protect themselves from inhaling harmful particles in polluted air in big cities and industrial zones for years.

But, there’s another reason people have been wearing masks in Asia for such a long time: to protect others when they themselves are sick. As a sign of respect for your fellow humans, when you have a cold – a virus – you wear a mask in public so as not to spread your illness to others around you. This practice is not as widespread in Vietnam as it is in other parts of Asia, such as Japan, but the etiquette still exists here, increasingly so among middle class families, like the ones I teach at my English language centre, in Ho Chi Minh City. On any given day, even before the pandemic, one or two students in each of my classes would come to school wearing a mask, because they had a cold and wanted to protect their classmates and teaching staff from the virus they were carrying.

When the coronavirus hit Vietnam and government advice on mask-wearing was issued, this was a no-brainer for many Vietnamese. Indeed, when such a fuss was made over mask-wearing in some Western countries, such as the United States, this baffled many Vietnamese I spoke to who simply couldn’t see the harm in wearing a mask, but could see the potential harm in not wearing one. Other Vietnamese friends I talked to were typically understanding of Westerners’ reactions to mask-wearing, recognizing certain cultural differences between here and there, which included a tradition of questioning those in power, and a different way of thinking that put a premium on the freedom of the individual over the community. The latter is generally not the case in Vietnam, nor in many other countries in this part of the world. For me, hearing some of my Vietnamese friends and acquaintances express sentiments such as this, was yet another reminder that people in Asia generally have a much better understanding of Western culture than people in the West do of Asian culture. And this imbalance is likely to cause a lot of problems and difficulties as we plough deeper into a century which will probably be defined by the economic rise of Asian countries and the economic decline of Western ones. Without an equal understanding on both sides of the others’ culture, confrontation and conflict are far more likely to occur.

Ultimately, mask-wearing would become a matter of contention and debate in many countries in the Western world, but not in East Asia and Southeast Asia. I admit to feeling slightly ‘silly’ when first wearing a mask in public during the very early stages of the pandemic. I felt conspicuous and self-conscious, even in Vietnam. I was concerned about my appearance: I didn’t what to look ‘funny’ or different. In the beginning, there was even a part of me that felt embarrassed about wearing a mask, because it might look like I was taking the virus too seriously, when really it was just a remote problem in another country that I’d seen on the news and become paranoid about and scared of.

For many people who were reluctant to wear masks, it seemed their main objections were based on appearance and inconvenience, rather than issues of effectiveness. The latter became an acceptable excuse for non-wearers, but was not the primary reason. Wearing a face mask is mildly inconvenient, somewhat uncomfortable, but most of all, it looks a bit funny. And, for men in particular, there’s a perception that wearing a mask makes you look weak. Although the latter attitude was also on display in Vietnam where, in the early stages of Pandemic Season, it was very noticeable that women were much more likely to wear masks than men, it was far more pervasive among Western males (including male politicians). Indeed, I was surprised to find out that many of my male friends in the UK were reluctant to wear a face mask. I see a parallel to this in the male perception of smiling in the UK versus that in Vietnam. Smiles come much more easily to Vietnamese men than to British, whom, I suspect, perceive the smile as a sign of weakness, submission and subservience, rather than of openness, hospitality and friendship.

Attitudes to mask-wearing in the West weren’t helped by muddled advice from medical experts and governments, many of whom ended up making U-turns on the subject: notable examples being, again, the UK and the United States. However, as mentioned earlier in this piece, if the virus had manifested itself in a more obvious and visible way – for example, a cloud of purple vapour issuing for a person’s nose and mouth – I’m confident we’d have all gotten over our issues with face masks long ago, be they based on vanity, individual freedom, or science.

[Back]

*

Psychology of Lock-Down:

As comfortable, secure and atypical as my lock-down context was, in terms of my emotional, spiritual and psychological state during this period, I expect my experience is far more relatable. After the upheaval and uncertainty of the months leading up to it, lock-down was a period of stillness, routine, rhythm and reflection. It was a time to process all that had happened since the turn of the decade, to catch-up with events as they unfolded across the globe, and to contemplate what the pandemic might mean for the future.

On the one hand, lock-down was characterized by a wistfulness and nostalgia for the pre-Covid era, but it was also a time of adaptation and action. Our lives had been fundamentally changed in many ways, so we were forced to adjust and innovate, especially with regards to work, family, social life and leisure activities. This was unnerving, of course, but it was also invigorating. A dramatic shift in the status quo required an equally dramatic change in the way we lived. Rather than descend into a state of ennui, many people I spoke to found that they became more active and alert during lock-down and the height of Pandemic Season. (As it turned out, feelings of ennui were far more common in the post-virus period in Vietnam, once the emergency appeared to be over.)

Every night in the bathtub in my hotel room in Vung Tau, I read aloud: sometimes for company, sometimes for entertainment, sometimes just to keep my vocal chords operating. I found myself drawn to books from my past and ones that advocated endurance and facing reality. Many of these were formative books from my teens, university years, and early twenties. I read Lattimore’s translation of ‘The Odyssey’, Homer’s epic poem about Odysseus’ return home from Troy: possibly the greatest story of endurance ever told. I read Sophocles’ ‘Oedipus Rex’, a play that offers no escape from reality whatsoever. (Indeed, there was something of a parallel between the present and ‘Oedipus Rex’, whose events unfold during a plague upon the city of Thebes.) I read ‘The Last Days of Socrates’, Plato’s tribute to his philosopher friend and mentor, and a memorial of his final days before drinking poisoned hemlock, a death sentence brought on him by the Athenian court, which he accepted unflinchingly.

I read anything I could by Hemingway, because I’ve always loved his style and he seems to me such a serious and sober writer. I read ‘Meditations’, the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius’s guide to Stoicism. I read ‘Siddhartha’, Hermann Hesse’s novel of spiritual awakening and asceticism inspired by the life of Siddhartha Gotama (The Buddha). And I finally finished reading Naomi Klein’s ‘This Changes Everything’, a critique of capitalism in the face of climate change. These books kept me company in the bathtub for six weeks of social-distancing and lock-down, and, I like to think, helped fortify my mind and spirit in order to endure Pandemic Season.

[Back]

*

The ‘Fight’:

In Vietnam, it was common for the government and media to portray action to contain the virus as a ‘fight’. Indeed, this was common around the world. But, if this was a fight, the enemy was invisible, and it was difficult to conceive of the threat of something one couldn’t see. To ‘fight’ suggested action. But how was one to act against an invisible enemy? I found this somewhat confusing and frustrating. If the virus was to be my generation’s ‘fight’, or at least a defining event that threatened our existence and way of life (climate change notwithstanding), how was I to take part? What was my role, my action in the resistance against the virus? Every ‘action’ we were told to take was passive and seemed more like inaction: stay home, self-isolate, social- and physical-distance: sit back and binge-watch Netflix. It felt as though, for the average person in this ‘fight’ against the virus, we were largely impotent.

Nor was there much of a sense of camaraderie or unity that one might expect to come from a mass struggle against a common ‘enemy’: people putting aside their minor differences and coalescing in order to fight a bigger, more significant threat. This wasn’t possible when best practices included not having contact with other people: not shaking hands, not hugging, not gathering, and not talking in-person. The goal was the opposite of community: it was isolation. Indeed, in this ‘fight’ your comrade might unknowingly be the enemy: might be carrying and spreading the virus unwittingly as a symptomless Covid-19 patient. Far from bringing us together, the coronavirus made us fear human contact and treat everyone with suspicion.

In turn, some of our world leaders and popular commentators proved depressingly incapable of uniting and coming together in the face of adversity, as Covid-19 became an increasingly politicized subject, with politicians and media outlets sometimes more concerned with pointing the blame for the virus than working together to contain it. Much like climate change, Covid-19 is a situation that no country is safe from and that no country can handle on their own. It wouldn’t matter if Vietnam had zero cases of coronavirus and the U.S had 100 million; Vietnam would still suffer the broader consequences of the pandemic despite its perfect record. Likewise, it wouldn’t matter if Vietnam achieved zero carbon emissions and the U.S continued to burn fossil fuels at the rate it does today; Vietnam would still suffer the consequences of climate change. Covid-19, like climate change, is a global issue requiring a global response. In these cases, no country can be an island. And yet, over the last 12 months, some of our world leaders and media outlets have continued to squabble about who is to blame – and even whom owes reparations to whom – for the pandemic. In this respect, if the global response to the coronavirus is anything to go by, there would appear to be little hope for climate and the environment.

[Back]

*

Taking ‘Action’:

Besides obeying lock-down regulations and heeding government advice on best practices, another ‘action’ one could take in the ‘fight’ against coronavirus, was to donate via one of several official channels to help the country deal with the pandemic. This was an ‘action’ I took (albeit in modest quantity). Subsequently, while in Vung Tau, I wrote a guide to How to Donate in order to help other foreign residents in Vietnam do the same. Indeed, many people I know also donated and, after publishing my guide, I received emails from people based in countries as far away as Europe who, having travelled to Vietnam in the past and fallen in love with it, also wanted to donate to help the country battle the virus. Part of the reason many people were so willing to donate was due to how successful the government’s response to the virus had so far been.

For a brief period in Vung Tau, the concept of herd immunity gave me some sense of purpose in the ‘fight’ against Covid-19. As I understood it, herd immunity involved the younger generation (with stronger immune systems and less at risk of contracting or suffering serious consequences from the virus) continuing to live and work through the pandemic – keeping the economy ticking over and services running – while the older generation (with weaker immune systems and more at risk of contracting and dying from the virus) continued to social- and physical-distance and stay home, until we either built-up a general immunity among the population or a vaccine was developed. Perhaps, then, it was the responsibility of people under the age of fifty to stay fit and healthy and thereby ‘fight’ the virus on behalf of the older population. Perhaps this was my generation’s chance to step up. Millennials, so often ridiculed for their lack of grit and stoicism compared to the generations that preceded them, and for their sense of entitlement and self-obsession, could be the selfless heroes of Covid-19. Millennials (my generation), could continue to work and actively stay fit and healthy through one of the worst pandemics in over a century in order to protect the lives of the baby boomers (my parents’ generation).

To some extent this imbued my lock-down routine in Vung Tau with purpose. My physical exercise took on a new role and a greater intensity: I swam, I ran, I did yoga, breathing techniques, and high-intensity interval training (HIIT). The small gym at the hotel where I was staying was closed because of the virus, but staff agreed to lend me some equipment so I could work out in my room. I ate fairly healthily, I drank lots of juice, I stayed hydrated, I tried to get enough sleep. I’m not particularly young anymore, but I’m reasonably fit, healthy and physically active. If maintaining my health and immune system during the pandemic was a way to participate and be proactive in the ‘fight’ against Covid-19, this was at least something I could do. I’m not suggesting these actions had any real impact on the wider situation, only that the concept made me feel less passive, less impotent, less of a bystander during lock-down, especially as I had parents both in their mid-seventies living in a country 6,000 miles away, where the virus was out of control. Physically and psychologically, it gave me something to focus on. My parents, too, made a conscious effort to remain physically active during their months-long lock-down in the UK: paying attention to their diet, general well-being, and trying to maintain a healthy immune system.

[Back]

*

Resistance & Compliance:

As the rules were tightened in Vung Tau, there were several occasions when I instinctively reacted with irritation and frustration when faced with restrictions and regulations that inconvenienced me or got in the way of my personal liberty. One example, among a few such instances, was when I went to meet my friends, Ben and Ruby, at their Airbnb apartment by the seafront, near Bãi Dâu beach. After parking my motorbike in the underground lot and walking up to the lobby, a security guard informed me that I was required to write my name and details, including my phone number and passport information, in the visitors’ log. All I wanted to do was go up to my friends’ apartment: a simple task. I didn’t need the hassle of all this formality and bureaucracy: I knew I didn’t have the virus, I knew I hadn’t been out of the country for over 4 years, I knew I’d been acting responsibly and within the current regulations: so why couldn’t the security guard just let me go in? I even suspected I was being unfairly scrutinized because I was a foreigner: would a Vietnamese visitor receive the same treatment, I wondered?