First published July 2021 | Words by Vietnam Coracle

This post was last updated 3 years ago. Please check the comments section for possible updates, or read more on my Updates & Accuracy page.

INTRODUCTION | CONTENTS | MAP | MEMORY

Sometimes referred to simply as ‘The General’, Võ Nguyên Giáp is a giant of Vietnamese history. Over his long life, Giáp participated in at least five wars across five decades against multiple adversaries hailing from five continents. Following his death, on 4 October 2013, Giáp’s state funeral and subsequent burial in his home province of Quảng Bình was an enormous national event: one of ceremony and sadness, but also an interesting mix of grandeur and modesty. Since then, millions have made the pilgrimage to Giáp’s tomb, myself included. When I visited The General’s tomb it was in unexpectedly unique circumstances and the experience has stayed with me. Although I intended to write about the visit, I had no images and very few notes. I was also mindful that, as with many important historical figures, Giáp is not universally revered: despite being largely adored in Vietnam, he still divides opinion, both domestically and internationally. Now, though, I’ve attempted to write the experience down. However, this is just a memory: I have no images to check and only a few notes from that day. As such, I cannot vouch for the accuracy of some of the details. But this is how I remember that visit to The General’s Tomb years ago.

[Back Top]

THE GENERAL’S TOMB: A MEMORY

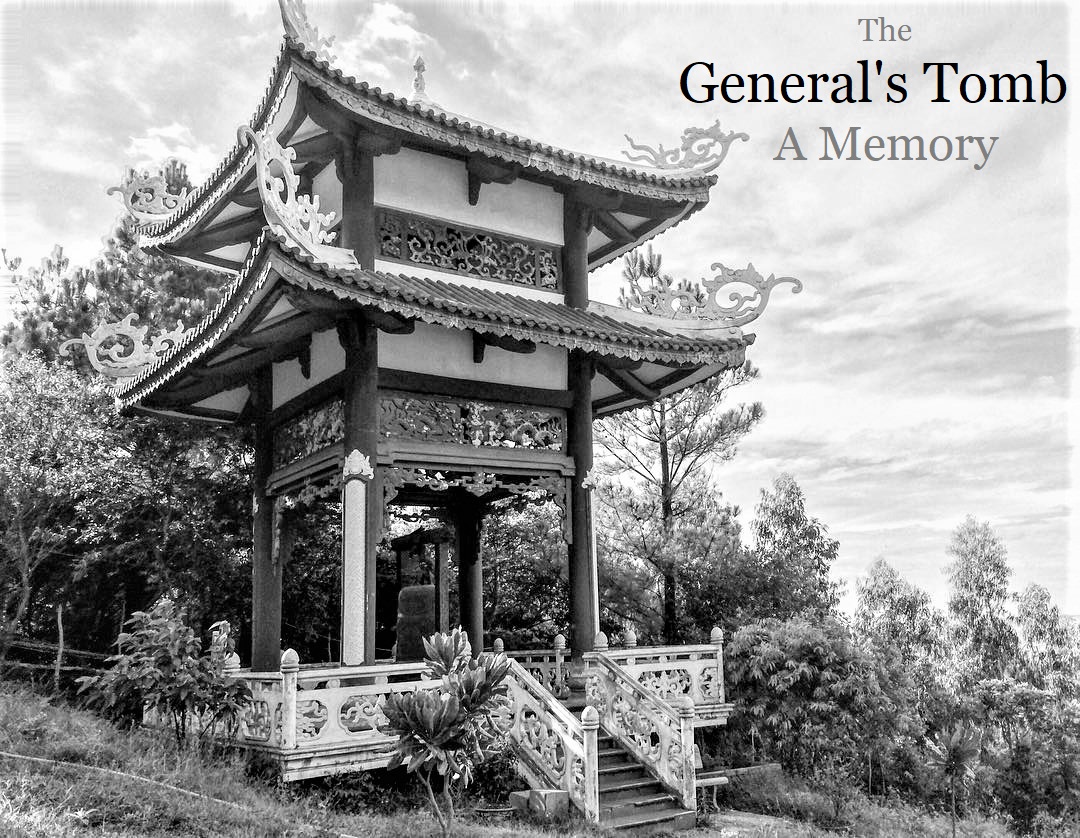

On this page, I’ve written a brief introduction to Võ Nguyên Giáp’s life and achievements followed by a long-form account of my memory of visiting The General’s tomb. This is intended to be a written piece without many illustrations. Any images on this page are not my own: I have ‘borrowed’ them from the Internet. As far as I recall I was not allowed to take photos at the tomb itself, or I was sufficiently moved by the site that I thought it inappropriate to do so. Regarding details on this page about Giáp’s life and actions, don’t take my word for it: I’m not an historian nor an expert on this subject. There are myriad interpretations and perceptions of General Giáp. This piece of writing only represents my own feelings at one point in time based on my own limited knowledge.

*Please Support Vietnam Coracle: I never receive payment for anything I write: all my content is free to read & independently financed. There’s no sponsored content whatsoever. If you like this article, please consider supporting the work I do. See my Support Page for details. Thank you, Tom

MAP:

Tomb of General Võ Nguyên Giáp, Quang Trach District, Quang Binh Province

View in a LARGER MAP

An Introduction to Võ Nguyên Giáp:

When Giáp died, on 4 October 2013, many people I knew in Vietnam referred to him simply as ‘The General’, such was his prominence in Vietnamese military history and his association with war.

Born on 25 August 1911 in Le Thuy District, Quang Binh Province in Central Vietnam, Giáp lived for 102 years. His life spanned a century of extraordinary change, conflict, political, social and military upheaval in Vietnam, of which he played a major role. In his youth he studied at Hue National Academy, where he was expelled for political activism. In his late twenties he became leader of the Viet Minh, formed to spearhead the resistance against French and Japanese control of Vietnam. He commanded the Vietnamese forces that defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, ending their colonial rule, and continued to serve in the military for much of the rest of his life. Giáp was deputy Prime Minister and Minster of Defence for four decades. Even in his late 90s, Giáp continued to voice his political and military opinions from his bed in a military hospital in Hanoi.

General Võ Nguyên Giáp served in the military for almost 50 years, with direct involvement in at least five major conflicts, including: World War II in the resistance against the Japanese occupation of Vietnam (1940-45), the Indochina War (1946-54) against the French colonial forces, the Vietnam War (‘American War’) against the American-backed South Vietnam (1955-75), the Cambodian-Vietnamese War (1978-79) against the Khmer Rouge, and the Sino-Vietnamese War (1979) against the Chinese during their invasion of northern Vietnam. His military and political career spanned six different decades. In all of these conflicts, the side on which Giáp fought ultimately prevailed.

A giant of Vietnamese history, Giáp was a military genius without any formal military training, whose influences – according to Giáp himself – were Napoleon, T. E. Lawrence (‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’), and Sun Tzu (‘The Art of War’). Intelligent, brave, ambitious and at times ruthless, Giáp’s military tactics led to events that changed the course of history in twentieth century Southeast Asia, chief among them the defeat of French colonial forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. His actions had an enormous impact on his own nation, but also on the wider world as the victory at Dien Bien Phu precipitated similar independence movements in other French and European colonies, such as Algeria. Indeed, many of the wars Giáp was involved in were ‘hot’ confrontations in the defining conflict of the second half of the twentieth century, the Cold War. Vietnam and the wars that were fought on its territory across four decades between multiple nations and armies, was a hotspot of the Cold War: a battleground on which the two competing superpowers (and ideologies) of the day, the United States and the Soviet Union, carried out proxy wars. Thus, Giáp’s military exploits in Vietnam rippled across the global political stage.

Giáp was a key figure in the Vietnamese military and politics for most of his long life, and he’s very likely to remain a towering figure in the nation’s history for centuries, perhaps millennia, to come. But history can have a way of cleaning things up – making people and events neat when really they were muddled, defining heroes and villains when really they were a complex mix of both. Among his many extraordinary achievements, Giáp did, as I suppose all military leaders must do at some point, some unpleasant things; things that were perhaps, given the context, unavoidable and necessary, but that nonetheless led to much human pain, suffering and death, both for his enemies and for his countrymen and allies. Let’s hope it will be a long time before anything like that is ever ‘necessary’ or ‘unavoidable’ again.

*Please note: Historical information in this article is based only on my limited reading & understanding of various sources & conversations with people: I am not an historian & I cannot vouch for the accuracy of historical details on this page. If you want to find out more about Giáp & Vietnamese history, I suggest you look at the history section of my Vietnam Reading List.

A Personal Memory at the General’s Tomb:

On 17 October, 2014, I visited Võ Nguyên Giáp’s tomb in Quang Trach District, Quang Binh Province, almost a year to the day after his body had been laid to rest there following a state funeral in Hanoi. At that time, The General’s tomb had already become one of the most-visited sites in Vietnam among domestic tourists, illustrating the level of respect and admiration many Vietnamese felt for Giáp and the extent to which his passing had affected much of the nation. Being in Vietnam when General Giáp passed away was, I imagine, like being in Britain when Churchill died in 1965. The nation paused, reflected and grieved for a man who’d played a significant role in military campaigns that threatened the survival of the country. Thousands lined the streets of Hanoi to pay their respects as the casket passed by; thousands more gathered at his final resting place on a mountainside by the ocean; and millions more came as pilgrims to the site of The General’s tomb in the following years to mourn him, pray and remember Giáp. People continue to do so today and probably will do for centuries to come.

*

After almost two months on the road, I start out early in the morning from a lonely guest house on the Ho Chi Minh Highway in Nghe An Province, birthplace of Ho Chi Minh himself. I plan to stop at his childhood home in Kim Lien, but the weather is cold, grey and wet, so I decide to continue south along his namesake’s road as far as I can, hoping to escape the bleak conditions. After several hours of riding I cut east, heading away from the mountains toward the coast where I pick up Highway 1, the nation’s main artery. The rain is falling heavily and the highway is in an awful state with patches under construction and articulated trucks hurtling through in clouds of spray.

I’m headed for Ngang Pass, the southern side of which is where Võ Nguyên Giáp’s tomb is located. Ngang Pass is one of four passes that historically divided what is now Vietnam into separate kingdoms at different points in history. The other three passes I know well, the most famous of which is Hải Vân Pass between Hue and Danang (the others being Cả Pass and Cù Mông Pass near Quy Nhon). I’ve only ridden Ngang Pass once and that was several years ago. Since then a tunnel has been constructed beneath the mountain, leaving the pass totally empty. But before I reach Ngang Pass, Highway 1 skirts a gigantic new industrial project: a Taiwanese steel plant on the coast. The area is a dust bowl. Much of the land has been ripped up or is in various stages of construction; trucks ply the dirt roads and thousands of men march from the site to cavernous canteens for lunch, fist fights breaking out along the way.

*

Two years later, in 2016, the Taiwanese company running this steel plant, Formosa, flushed large quantities of toxic industrial waste into the East Sea, poisoning the ocean, killing a hundred tons of fish which washed up dead on the beaches, and destroying the livelihoods of thousands of families along the central coast, whose survival depended upon the ocean and its fish. It was one of the worst environmental disasters in Vietnam’s history. Still today, many people are nervous to swim or fish on this stretch of coast. And all this within sight of the tomb of one of Vietnam’s staunchest protectors, who had himself, at almost a hundred years of age, in 2009, spoken out against the potential ecological destruction and military insecurities that would result if plans went ahead to let Chinese companies mine bauxite in the Central Highlands, which, despite Giáp’s protests, they eventually did (see Dak Nong Geopark Loop.)

*

Highway 1 disappears into the tunnel, but I veer left before the entrance and start to ascend the Ngang Pass. The traffic fades and the road climbs through eucalyptus trees, offering brief glimpses of the ocean from the apex of hairpin bends. I stop by a stream to wash the soot from the highway and the steel plant off my face, arms and legs. As an ancient barrier between Vietnam and the Kingdom of Champa, Ngang Pass was once a military flashpoint and the site of a famous battle between the two states. It’s still a border today, separating the provinces of Hà Tĩnh and Quảng Bình. Such was the importance of this pass that it features in Vietnamese poetry, folktales and mythology. An imposing gate dating from the Nguyễn Dynasty marks the summit of the pass with views across the mountainous bluff that it traverses. In terms of scenery, Ngang is the least spectacular of Vietnam’s four historic passes, but its historical significance and military associations make it a fitting backdrop for the tomb of one of Vietnam’s greatest war heroes. Indeed, Giáp himself chose this location as his final resting place, in the province of his birth.

*

The last 2,000 years of Vietnamese history has seen a great many military heroes. The Trưng sisters rose up against the Chinese Han Dynasty in the 1stst century CE; Ngô Quyền defeated the Chinese during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in the 10th century; Lê Lợi defeated the Ming Dynasty in the 15th century; Trần Hưng Đạo in the 13th century defeated Kublai Khan and the Mongol Empire; and Quang Trung defeated the Chinese Qing Dynasty in the late 18th century. During his long life – spanning most of the 20th century – Giáp had a hand in defeating the Japanese, the French, the Americans, the Khmer Rouge and the Chinese. In a nation with a long history of celebrated martial leaders, Giáp may well go down as the greatest Vietnamese military commander of them all. And, just as Vietnam’s military figures from centuries past are still venerated and worshipped as deities in temples, shrines and tombs across the nation today, so too, I imagine, will Giáp’s tomb on a lonely hillside overlooking the sea in the shadow of Ngang Pass, continue to be a sacred place of pilgrimage for Vietnamese for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years to come.

*

After descending Ngang Pass I turn off onto a newly laid slip road heading east along a lip of land between a forested hillside and the ocean, leading toward the tomb of the late general. The road is lined with floral wreaths and framed portraits of The General in military uniform; makeshift roadside shacks are crammed with incense, votive offerings and Giáp memorabilia. It’s midday. The sky is grey and a sea mist hangs over the promontory. The air is muggy and soporific. All the shopkeepers are asleep in their hammocks, enjoying their siesta. There are no lines of mourners, no coaches depositing pilgrims, no officials standing guard: it’s eerily quiet – not what I was expecting from one of Vietnam’s most-visited sites.

Despite Giáp’s place in the pantheon of Vietnamese military heroes, his tomb is modest, understated and serene, movingly so. The complex occupies a beautiful position on the lower slope a forested hill jutting into the sea – the southern point of the same mountainous spur that the Ngang Pass negotiates. I park my motorbike in an empty gravel lot where a couple of exceedingly polite uniformed officials put my bags in a locker and check my passport. Giáp’s death being relatively recent, the ramp leading to his sarcophagus on the hill is still under construction and yet to be paved. Instead, a gravel pathway curves up the slope before transitioning to a wooden walkway. On the right, perched on the hillside in a clearing among pine trees, is a pavilion housing a large traditional bell looking out over the East Sea. For now, these are the only structures to have been built on the site.

The layout of Giáp’s tomb is simple and elegant. A modest monument to a man whose life and actions had a profound impact on the nation. Like the tombs of Vietnamese emperors in dynasties past, the site was chosen by Giáp himself and based on the principles of phong thủy (geomancy, better known as feng shui). The bell tower on the hillside is in a commanding position, looking over land and sea. A short walk beyond the tower, Giáp’s sarcophagus faces east to the rising sun. Another reason for the tomb complex facing out to sea might be as a warning against any future military incursions into Vietnamese territory. Just as all statues of Trần Hưng Đạo (the military general responsible for a great naval victory over the invading Mongols of Kublai Khan in the 13th century) depict him facing the direction of the ocean, pointing a finger towards it as if to say to potential invaders “Sail back from whence you came”, so too Giáp’s tomb stands on the threshold of the Vietnamese mainland as a reminder to foreign invaders. It may also be significant that the bell tower and tomb face the direction of the Hoang Sa (Paracel) Islands, the possession of which is disputed by Vietnam and China, sporadically igniting fierce nationalist sentiment whenever China makes a move on the territory, and is a potential catalyst for military conflict between the two nations.

*

Although I don’t have any great depth of knowledge about Giáp, his life and his military exploits, I do admire some of what I know about his achievements and respect his place in the pantheon of Vietnamese military leaders, not to mention the sheer breadth of historical events that his long life spanned, many of which he was directly involved in. The Vietnam that Giáp was born into and grew up in from 1911, when the country was firmly under colonial rule as part of French Indochina, is in stark contrast to the one he departed from in a military hospital in Hanoi in 2013, with Vietnam an independent nation riding a wave of economic growth and prosperity on the back of more than 20 years of rapid industrialization. The political, economic, social, and cultural differences between Giáp’s youth and old age are vast. Living in Vietnam when Giáp passed away, it was impossible not to sense the national grief, even in Saigon, as I was, where Giáp is perhaps not quite as widely admired as in other parts of the country.

*

After passing the bell tower, I continue towards The General’s tomb. Another polite uniformed official hands me three incense sticks, already lit. I walk along the wooden platform and place them in front of Giáp’s sarcophagus, embedded in the hillside, surrounded by wreaths and flowers. This is the extent of Giáp’s mausoleum: a bell tower and a tomb. I stand there for some time, thinking about Giáp and how much Vietnam – its people and its land – endured over the one hundred and two years of The General’s lifetime. I’m all alone in front of his sarcophagus. Incense wafts over from the altar, mixing with the floral scent of the wreaths; from the hills, pine and eucalyptus fill the salty air. I can hear rollers crashing on the sandy beach below. There’s a small island just offshore, a coracle moving towards it. No one is here: just me and the military guard. A far off peal of thunder reaches the tomb from somewhere out at sea. I can’t help but think of the cacophony of gunfire and heavy artillery that must have echoed around the battlefield at Dien Bien Phu over the seven weeks that Giáp’s forces laid siege to the French positions in the valley, from March to May 1954. That valley is quiet now and so is The General’s tomb.

*

Giáp was a military leader responsible for many great victories, some of which changed the course of Vietnamese history. But, as with all military victories, they came at great human cost, both for his adversaries (many of whom were fellow countrymen) and his own side. At Dien Bien Phu, for example, Vietnamese casualties were at least four times higher than those of the colonial forces. Indeed, reading about some of the tactics Giáp employed – not only against military opponents, but political ones too – it’s difficult to continue to romanticize or idolize him. But, given the social and political context in which Giáp grew to manhood and under which he personally suffered, it’s hard to conceive of any alternative to the long and bloody military struggles of his lifetime. When Giáp was in his early 30s he discovered that his wife had been beaten to death by guards in Hanoi prison, his sister-in-law guillotined, and his daughter died in prison under suspicious circumstances. This is but one example of the many injustices suffered by Vietnamese under French colonial rule. In such circumstances, it’s not difficult to imagine what motivated Giáp, among many others, to lead a charge for independence, however costly that might be.

*

As I’m standing in front of Giáp’s tomb, I hear voices coming up the hill. A group of young Vietnamese women are walking along the gravel pathway, past the bell tower, towards the sarcophagus. As they reach the top and the military guard hands them sticks of incense, the group spot me and shout “Hello!”. I’m conspicuous as the only other pilgrim at the site, but also as a foreigner. I turn to leave, thinking it might be inappropriate to be standing here so long, especially when other mourners are about to pay their respects. But I decide to stay on the platform a little longer to see how the women will act in front of the tomb.

I watch as they casually take the incense sticks handed them by the official, plant them in the altar and walk on past the tomb toward me. There’s no formality, no praying, no deference. In fact, the women are in high spirits, as if they were on a fun day out. This is nothing like the sombre mood at Ho Chi Minh’s austere mausoleum in Hanoi, where a certain level of solemnity is essentially enforced by guards, and a code of conduct regarding etiquette is generally adhered to by visitors. For the women at Giáp’s tomb, it seems as though visiting the mausoleum and paying their respects to The General is something they feel compelled or obligated to do, but not necessarily to treat with sadness and formality. I’ve noticed a similar atmosphere at other such sites in Vietnam. At the battlefield at Dien Bien Phu, for example, there’s no solemnity, emotion or even quiet contemplation, at least not externally, even among veterans of the battle itself. At Giáp’s tomb, the women seem more interested in having their photo taken with me than anything else. Each of the group takes turns standing next to me, their cameras pointing away from the mausoleum. I feel uncomfortable and shoot a glance in the direction of the military guard to see if I can register any annoyance in his demeanor. He seems uneasy, but his countenance remains blank. Eventually, I depart with the group back down the hill toward the parking lot, chatting about life and work in my broken Vietnamese.

As I mount my motorbike to leave, three coaches arrive, each depositing some 50 pilgrims at the base of the mausoleum. Comprised of all ages, the pilgrims assemble into groups amid a buzz of excitement. Each person wears a brightly coloured baseball cap denoting the group they belong to. Amidst much chatter, the 150-strong group begin the walk up to the bell tower and Giáp’s sarcophagus, kicking up a cloud of dust behind them. I ride off, rejoining the blighted course of Highway 1 toward Dong Hoi City. Thus, Giáp’s tomb is flanked to the north and south by bleak, busy industrial zones: the Formosa steel plant north of the Ngang Pass and the truck-strewn Highway to the south. But the mausoleum itself is a place of serenity, beauty and contemplation. In a very Vietnamese way, Giáp’s tomb combines commemoration with celebration: the sombre and serious nature of the site is softened – but not undermined – by the informality with which it’s treated. The lack of pageantry and enforcement of etiquette, in my opinion, makes The General’s tomb a more human and moving monument.

*Please note: Historical information in this article is based only on my limited reading & understanding of various sources & conversations with people: I am not an historian & I cannot vouch for the accuracy of historical details on this page. If you want to find out more about Giáp & Vietnamese history, I suggest you look at the history section of my Vietnam Reading List.

Please Support Vietnam Coracle: I never receive payment for anything I write on Vietnam Coracle: all my content is free to read & independently financed. There’s no sponsored content whatsoever. If you liked this article, please consider supporting the work I do. See my Support Page for details. Thank you, Tom

[Back Top]